OG Anunoby stands on top of multiple fault lines in the NBA. On one hand, he is the answer to an important question: what does a breakout season look like when it happens for a team much worse than the season before? At the same time, he answers what a breakout season looks like when it’s hardly accompanied by a jump in scoring average.

Our ideas of improvement in the NBA are tinged by the points column. There’s of course much more that happens on the basketball court than scoring, but you wouldn’t know it if you looked at the NBA’s historical awards for Most Improved Player (MIP).

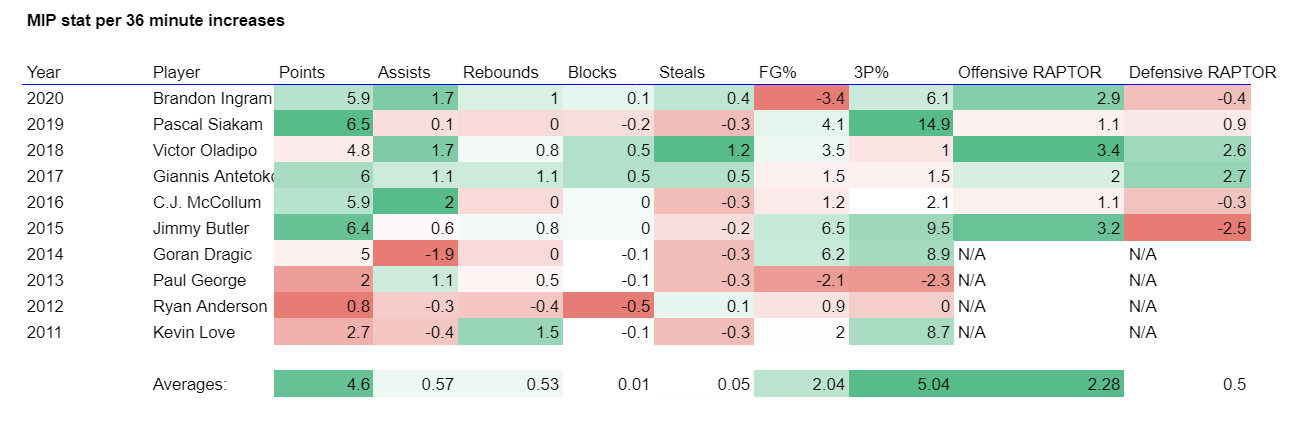

There’s almost no correlation between an improvement in rebounding, passing, or defensive numbers and winning the MIP award. There is, however, a correlation between players who win and improvement in the categories of per-36 scoring and efficiency. That’s what a breakout year usually looks like, according to NBA award voters.

By those standards, Anunoby’s season actually looks somewhat like that of a MIP, albeit most similar to some of the least impressive seasons of the past decade to have won the award.

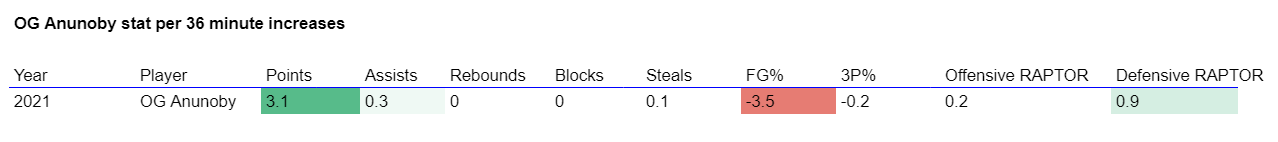

However, if you dig deeper into Anunoby’s season, the contexts through which he’s improved look little like MIP. For one, he’s taken more of a leap defensively than offensively, according to the advanced metrics. That was true only of one MIP player of the last decade, Giannis Antetokounmpo, in 2017. That’s not to say that Anunoby is a competitor for the MIP award this season. He’s not, although last year, his overall RAPTOR leap of plus-3.9 was actually superior to four of the last six winners. But the point is rather that the manner in which Anunoby is improving looks similar on the surface but ultimately different from the league’s general definition.

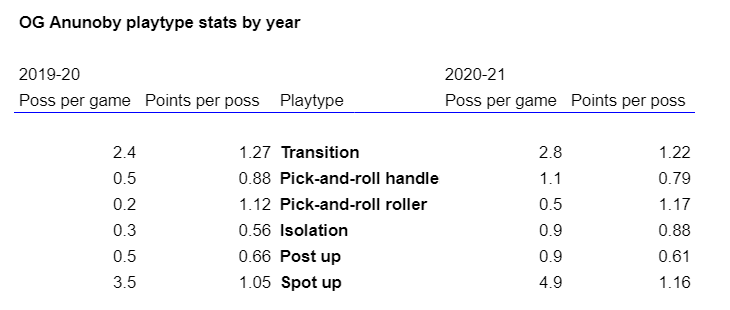

For one, Anunoby hasn’t really increased his game with the precise scaling that is easily identifiable as improvement. Take Brandon Ingram last season, for example. He improved his efficiency in the pick and roll while also expanding his reps there. That was a focused specialization; Ingram actually spent less time in the post and virtually the same amount of time in isolation in his MIP year, despite taking 3.7 more shots per game. Inherent to the NBA’s idea of improvement is specialization, or at least spending more time doing the stuff you do well and less time doing all the other nonsense.

Yet Anunoby has expanded in the opposite direction. He’s more entropic than the standard NBA definition of improvement, more random. Rather than specializing this year, he has become the platonic ideal of a generalist on both sides of the ball. There hasn’t been a single area of key improvement for Anunoby. Rather, he’s added shots from all over the floor, increasing his frequency across the board. There’s been no single efficiency leap, either, for one playtype.

All told, Anunoby’s efficiency has been virtually the same this year as last. He’s improved his percentages from all three areas of the court — at the rim, from the midrange, and from deep — but his shot spectrum has become slightly less idealized, as he’s taken fewer shots at the rim and more from the midrange.

“His shooting, his numbers are probably down a little bit but it’s improving, anyway,” explained Nick Nurse. “He’s shooting a variety of shots rather than just kinda the wide-open corner ones.”

There’s nothing wrong with that; it’s an indication that Anunoby is doing more to create for himself. But he’s doing it from all over the floor, in all different sorts of ways. Generalist.

On the defensive end, Anunoby is more effective because the team relies on him more heavily. Whereas last year the Raptors had two good centers in Marc Gasol and Serge Ibaka, this year the Raptors have zero. That has meant far more of Anunoby defending the rim on the defensive end. Yet he remains the team’s primary wing stopper and is capable of switching onto almost any guard. As a result, his matchup versatility ranking has never been better; per BBall Index, Anunoby is the most versatile defender in the NBA this season, splitting his time relatively equally defending all positions, spending at least 15 percent of his time on all positions.

It’s an indisputable fact that Anunoby is having a better defensive season this year than last. His individual numbers, on-off numbers, and advanced metrics all tell the same story. A year ago, Toronto asked Anunoby to defend elite wings, which job he performed admirably. Now he defends elite players no matter the positional designation. Again: generalist.

Anunoby does everything on the defensive end, from defending the point of attack to switching to helping clog the floor to doubling to protecting the rim as help to wrestling with bigs in the post to, well, everything. You get it. Yet the Raptors are a dramatically worse defensive team this season than last. What does that mean for Anunoby? It doesn’t invalidate his improvement, but one would surely want a player’s improvement — particularly one of a team’s most important players — to correlate with his team getting better at the same time. It’s not Anunoby’s fault that the team defense has collapsed around him, although it should give us some sense of how the quality of team defense often is decided by the weakest link rather than the strongest. Anunoby has decidedly not been the weakest defensive link this year. Beyond that, Anunoby didn’t have a huge area within which to improve; he was already a pseudo-All-Defense caliber defender last season. This season he’s just seen more defensive usage, and he’s continued his elite level in those various roles.

Those are the areas in which Anunoby’s game has changed. To repeat, I’m not calling for his inclusion in the MIP debate, but it’s worth asking whether the form in which he’s improved is more or less valuable than the NBA’s more traditional path for development.

Put another way, is specialization or generalization more helpful in the long-term for player development? Let’s set the table in terms of concrete skills: Is it more important for Anunoby to be an elite roll man or an elite spot-up shooter? The former requires him honing his screening, passing, and finishing skills inside the arc while the latter requires off-ball movement, shooting, and driving against rotations. And both jobs require a player standing in very different areas of the floor. Which means — and this may be too obvious to merit saying — that he can’t do both on the same possession. So there’s some element of opportunity cost to generalizing, at least at the micro level from one possession to the next.

But Anunoby’s ability to fill multiple roles actually unlocks Toronto’s ceiling at the macro level. A player who can spot up and run secondary pick and rolls as a shooting guard, or bang with centers and set screens as a center allows a team to play all sorts of different kinds of ways. To have those kinds of players, a team would generally have to pay two salaries. In Anunoby, Toronto has a player who can fill all sorts of different roles all under one modest (read: underpaid) price tag. Anunoby is a necessary condition for the Raptors to play small. The same if they want to throw a defensive group on the floor, or one that maximizes shooting, or the transition game.

In fact, there’s no optimized iteration of the Raptors that doesn’t have Anunoby on the floor. That’s not true of most specialists. I wrote this last year of Anunoby’s spidered path to improvement:

Anunoby is not taking the road to stardom that is most traveled. He is not expanding his off-the-dribble game, learning to launch pull-up triples and beat opponents to the rim. But he is expanding the frame of contexts within which he can succeed. For the Toronto Raptors, in 2020, that’s probably more important than him becoming a ball-dominant scorer. The rest can come later.

We are seeing the logical extension of that path. Anunoby continues generalizing, and he continues offering more contexts within which he can succeed. At some point, one of the expansions has to stick; currently, Anunoby shows flashes across the board, but in any single game he’s most likely to offer defense and shooting. That’s plenty valuable, but many of his orbiting skills don’t rear their heads from game to game. We still don’t know what the finished product will look like. But we can say with a fair amount of confidence that he’ll offer star-level impact, no matter his role, when he reaches his peak. He already does that, and his added skills only continue sharpening.

At the same time, we may see very little of Anunoby for the rest of the season. According to the injury report, he is still rehabbing his calf, and that rehab may hold him out of more games than absolutely necessary. He may only end up playing in just over half of his team’s games. That would surely hold him out of any awards conversation, but describing a year as ‘breakout’ isn’t an award at all.

So what does a breakout season look like? Long answer: it depends. The NBA would have you believe improvement is when a player picks a role and maximizes it. That certainly is one form of breaking out, but Anunoby is taking it more literally, in that he’s breaking out of whatever box in which your conception of his player type might have contained him. He’s not perfect at every job yet. His post-ups may end in stumbling turnovers, but he’s starting to learn to put his body through his opponents and finish with ease. His driving footwork is cross-eyed at times But the more reps he gets at such tasks, the faster he’ll recognize patterns, and the easier they’ll become. The jagged edges will become smoother, or even will become weapons he can utilize. When Anunoby’s Twilight Zone footwork becomes something that trips opponents and allows him to power through their bodies, that’s when he’ll reach his platonic ideal.

That’s all in the future, of course. This year, we’re seeing the kernel of that. The planting of the acorn. The tree into which Anunoby blooms is as yet undecided. The twists of the branches, the runic patterns on the bark. Anunoby is far from fully formed. But the bough is shooting up, faster than ever. That’s the breakout we’re watching this year. And that’s how Anunoby is upending what ‘breakout’ traditionally looks like.