While everyone else is getting ready for their Canada Day (or July 4) long weekend, the basketball world will be at the starting line of the 2017-18 season, champing at the bit to strike first in free agency, leverage another (and, for now, final) increase in the salary cap. Free agency begins at the stroke of midnight late Friday/early Saturday, and with it we venture further into the New TV Money Era, where a lucrative national rights deal has pushed the NBA’s salary cap from $70 million to $94 million and now $99 million, based on the latest reports. From here, it’s expected to level off, and while many teams appear to be stockpiling cap space for a more loaded free agent class in 2018, there’s ample money to be thrown around over the next few weeks.

Despite the increase, the salary cap is coming in at a level below expectations. It was once estimated at $103 million, and while $99 million is a small decrease in percentage terms, it also lowers the luxury tax and tax apron lines, which figures to make life difficult for the Toronto Raptors. Like the cap boom happened at a somewhat unfortunate time on the team’s upswing, the lower tax threshold threatens the team’s flexibility in a pivotal summer. With big money committed to DeMar DeRozan, Jonas Valanciunas, and DeMarre Carroll already, president Masai Ujiri and staff will have to unload a salary, negotiate below-market deals for their four unrestricted free agents, or make some tough decisions on which of those free agents takes precedence. (This says nothing, of course, of the much larger overarching decisions about which direction the franchise should be heading.) There are means of clearing cap space, and the Raptors are oddly in a better position to retain key pieces than last summer (when their team salary was lower but the options available to them fewer) if they can afford it.

All of this will require some careful salary gap gymnastics. Luckily, the Raptors’ front office is well-staffed to execute such machinations, with former league cap adviser Bobby Webster expected to assume the title of general manager any day now, Ujiri possessing a strong track record of landing bargain fliers, and a strong player development staff making sure the inexpensive back end is ready to contribute where the offseason agenda may leave a hole. Still, it won’t be easy, and something on the roster will surely have to give.

What follows is an explanation of the contract situations and cap rules that the Raptors face right now. This is the fourth year in a row I’ve done this post in the hopes of helping readers understand why certain moves can or can not happen, and how they may come to pass. The league has a new collective bargaining agreement kicking in on July 1, so this will be a little different than prior years, although not significantly. Some of it will be in less detail than is necessary for a thorough understanding and some of it will be in more detail than is necessary for a cursory understanding (apologies if I haven’t correctly navigated that middle-ground) – if you have any questions, tweet them to me @BlakeMurphyODC or email them to me at eblakemurphy1@gmail.com, and I’ll do a follow-up post explaining certain rules or scenarios.

Note: All salary data comes courtesy of Basketball Insiders or my own calculations based on the new CBA document. (Yes, I have read the entire thing now. I don’t recommend it.) Normally, I’d throw a shout to CBAFAQ.com here, but Larry Coon’s indispensable guide is yet to be updated for the new CBA. Most of the information there is still useful for these purposes, though, and that site should be your first stop for all questions. The lack of CBAFAQ update to help means that there’s a chance I’ve misunderstood something going through the CBA myself, and I’ll update accordingly. Also, a thanks to Daniel Hackett, who I have probably clarified some of this stuff with at some point as we figured out the new climate, and to Cole Zwicker, who helped me clarify an area.

Contracts, holds, and explanations

Contracts

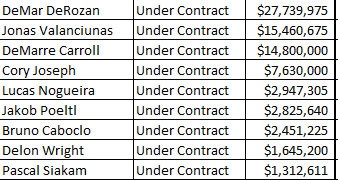

The Raptors have the following contracts on their books for 2017-18:

One new note to make this year is that players on non-guaranteed contracts now count for only their guaranteed amount in the outbound salary part of trades, not the full non-guaranteed amount. This doesn’t matter much for low-salaried players like Powell and VanVleet who wouldn’t bring much salary back, anyway, but it could come up if, say, a Kyle Lowry gets a partially guaranteed fifth year on a new deal.

(The amounts for Siakam will change in a second – see the Big Picture subsection below.)

Unrestricted Free Agents

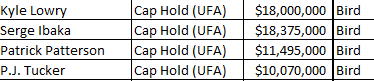

The Raptors have the following unrestricted free agents, with their cap holds and rights types highlighted:

(Note: The Raptors also have a UFA cap hold for Jason Thompson left over from 2015-16, which I initially forgot to include. It’s pretty meaningless – he won’t be back, and if the Raptors blow things up, they’ll renounce his rights and clear it, anyway. Bookkeeping wise, it remains, because you don’t renounce these things until you need to.)

Having those expiring contracts doesn’t necessarily give the Raptors cap space. Until the rights to those players are renounced, the players have cap holds, which count for the purposes of the salary cap to prevent teams from signing a bunch of free agents with cap space and then signing their own guys. In many cases, ordering signings in that way can still be beneficial, but for the Raptors, they would need to renounce a lot of rights to clear up space.

The usefulness of lower cap holds isn’t much in play for Toronto here, but the Bird rights they hold on each player are. Full Bird rights allow a team to exceed the salary cap to re-sign their own player up to the maximum contract. So the Raptors can’t really find their way into much cap space through helpful cap tools (like reasonable cap holds) to pursue high-end free agents from other teams, but they can use rights to go well over the cap to keep their team together.

(Early Bird and Non-Bird rights also exist and allow teams to exceed the cap to re-sign their players up to certain raise amounts, but the Raptors hold full Bird rights on each of their free agents, so we won’t go into those here.)

Each of these cap holds exist until the Raptors renounce their rights or the players sign new deals. In reality, the team would only renounce rights if they required the cap space that doing so creates, which would only be the case in the “blow it up” scenario. The specifics of the cap holds aren’t that important this year, except to explain why the Raptors don’t have cap space even when their total salary is currently below the cap.

As an aside, Drake is also a free agent, but global ambassadors don’t have cap holds.

Restricted Free Agents

The Raptors have the following restricted free agents, with their cap holds highlighted:

![]()

Yes, that Nando De Colo. The Raptors still own his rights in restricted free agency (and his Early Bird rights), even though he’s playing on a multi-year deal with CSKA Moscow. If the Raptors want to retain his RFA rights, they’ll need to issue him a $1.83-million qualifying offer by June 30, one that will stay on the books all summer (note that I used his cap hold amount rather than his $1.83-million qualifying offer) unless the Raptors rescind his rights.

This is mostly just a bookkeeping note – De Colo isn’t coming over, but if their offseason maneuvering allows, the Raptors may be able to maintain his rights and keep him on the books through the summer. In an offseason in which they don’t figure to have cap space, anyway, there’s little cost to issuing him a qualifying offer to retain his rights. I wrote more about this here.

Non-guaranteed Deals

The Raptors have the following non-guaranteed deals:

Powell’s deal guarantees on June 29, VanVleet’s on July 20. These can often be helpful for the purposes of flexibility or if a deal doesn’t work out, but as I wrote a few weeks ago, letting these deals guarantee is about as close to a no-brainer as it gets. They can be considered regular contracts for our purposes.

One new note to make this year is that players on non-guaranteed contracts now count for only their guaranteed amount in the outbound salary part of trades, not the full non-guaranteed amount. This doesn’t matter much for low-salaried players like Powell and VanVleet who wouldn’t bring much salary back, anyway, but it could come up if, say, a Kyle Lowry gets a partially guaranteed fifth year on a new deal.

Kennedy Meeks has been signed to an Exhibit 10 deal with a $50,000 base compensation, but Exhibit 10 bonuses do not count for the purposes of the team salary calculation. Two-way contracts, if and when the Raptors give them out, also don’t count in the team salary calculation.

Also off the Books

The small guarantees paid to Brady Heslip, Jarrod Uthoff, E.J. Singler, and Yanick Moreira from last year are cleared from the ledger as of July 1.

Draft picks

The Raptors have the following first-round draft picks, with their cap holds highlighted:

In a new CBA wrinkle, the cap hold for first-round draft picks is now equal to 120 percent of the rookie scale amount for that draft slot. This is because in almost all cases, first-round picks sign for 120 percent of scale. Anunoby is unlikely to be any different, but if he signed for less, his cap number would decrease accordingly. Once Anunoby signs his deal, he can’t be traded for 30 days.

New CBA wrinkle – Two-way contracts

Starting this year, NBA rosters are expanding to 17 with the addition of a pair of two-way roster spots. On one of these deals, a player will receive a higher D-League salary for their time spent in the D-League and a prorated amount of the NBA minimum while in the NBA. Time in the NBA is capped at 45 days during the regular season, plus any time before the start of D-League training camp and after the conclusion of the D-League regular season. These players are not eligible for the NBA playoff roster, though the team will hold the option to convert the two-way contract to a regular NBA contract at the minimum (for that player’s service time) at any point. This could be a post of its own. And in fact, it is.

The big picture

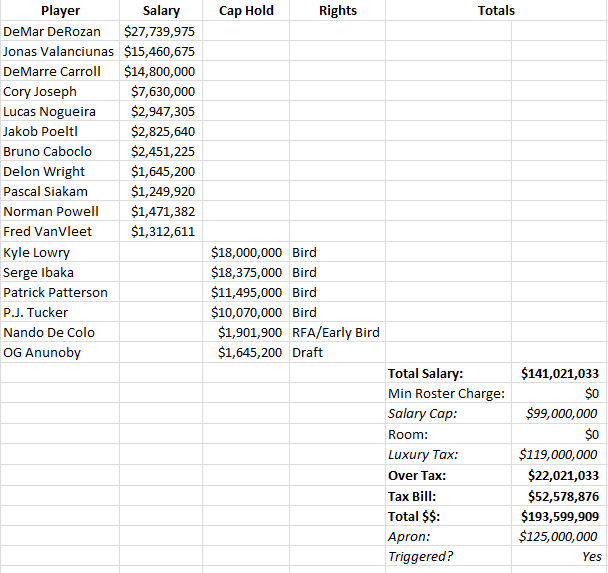

Here’s how the Raptors’ cap sheet looks at present:

I couldn’t decide if the luxury tax calculation was worth including in this post or not. The tax is charged on an escalating marginal basis, such that the first $4,999,999 is taxed at $1.50 per dollar, and the tax increases for each subsequent $5-million block. It’s basically an escalating penalty the further over the tax you go, to where trimming, say, $14.8 million could wind up saving the team significantly more depending on which tax block they sit in at the time. We’ll go into some of these scenarios in the coming weeks as we update the cap sheet. A note: The luxury tax owed is calculated based on the roster for Game 82, so the Raptors could conceivably enter the season well into the tax and get under it later in the year.

You’ll notice here that the amount charged for Siakam is slightly lower than in their salary sections above. That’s because the new CBA bumped up the league minimums and rookie scale amounts. For league minimum contracts like VanVleet and Powell, both the actual salary and the salary for the calculation gets bumped. For players on rookie scale deals, though, the old contract amount counts for cap/tax purposes. This is the smallest of details, but depending on how deep into the tax the Raptors go, it could wind up being a difference of a couple hundred thousand in tax payments. There’s some confusion on exactly how this works in the new CBA, so it may be best to just ignore it until we have some clarity, given how small the impact is to the team’s real flexibility.

The cap sheet above isn’t all that helpful for offseason planning, because, well, there’s no way they’re going to rival the largest payroll of all time. We also don’t need to include De Colo in any “still be good” scenarios, because his hold won’t count toward team salary and will eventually disappear when the qualifying offer expires.

For illustrative purposes, this is what the cap sheet would look like if they renounced the rights to all of their free agents (the “maximize cap space” or “probably blow it up” scenario):

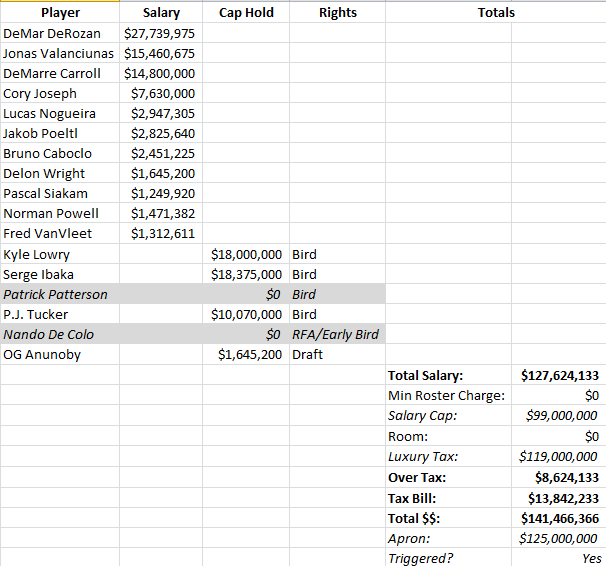

We could go into a bunch of different scenarios in between. I won’t do that. It’s too many screenshots. To illustrate, though, we’ll do one more, which is where the Raptors hope to retain Lowry, Ibaka, and one of Patterson or Tucker.

This scenario not only has the benefit of being just 15 players, but I think it’s a reasonable salary and tax payment amount for readers to keep in mind.

I think the team would probably like to stay under the $125-million tax apron, which would mean spending only an estimated $44.68 million on their three free agents (or that amount, plus any salary they can shed – an article of its own). Going over the apron restricts flexibility in terms of available exceptions, taking on salary in trade, sign-and-trades, and protections on restricted free agents. The total team salary is also calculated a little differently for the apron (cap holds are excluded, unlikely bonuses count in full, and some other wrinkles), but this is outside of the scope of this article – it will be worth it’s own discussion later in the summer if the Raptors appear set to cross that mark.

However the specifics shake out, it’s unlikely the Raptors have cap space if they intend to remain competitive, barring some selling off of pieces.

Exceptions

There are sometimes scenarios in which it makes sense for a team to stay above the cap. If the Raptors opt to do so (which they almost certainly will), they open themselves up to the non-taxpayer or taxpayer mid-level exception. They would also have the bi-annual exception if they’re below the tax apron. If the Raptors duck below the cap at any point, they’ll instead have only that cap space and the room mid-level exception.

Get under cap

If the Raptors go under the cap by renouncing multiple free agents, they’ll have the following:

Cap space: Depends on how many free agents they lose/renounce, but up to an estimated maximum of $17.8 million

Room mid-level exception: $4.328.000 (one- or two-year deals with a 5-percent raise; can be split between players)

Stay above cap, below tax apron

If the Raptors stay over the cap as outlined but below the tax apron (after using the exception in question), they’ll have the following:

Cap space: $0

Non-taxpayer mid-level exception: $8,406,000 (up to a four-year deal, with raises of 5 percent of the first-year salary; can be split between players)

Bi-annual exception: $3,290,000 (one- or two-year deals with a 5-percent raise; can’t be used two years in a row; can be split between players)

As a side-note, if a team uses the Bi-Annual Exception, the apron becomes a hard cap the team can’t cross for the rest of the season. If they use more than $5,192,000 of the non-taxpayer mid-level exception, the apron becomes a hard cap. (The hard cap at the level of the apron is also triggered if a team acquires a player in a sign-and-trade, for those trying to get sneaky.)

Stay above cap, reach tax apron

If the Raptors stay over the cap as outlined and an exception would push them above the tax apron, they’ll have the following:

Cap space: $0

Taxpayer mid-level exception: $5,192,000 (up to a three-year deal, with raises of 5 percent of the first-year salary; can be split between players)

As a note, these exceptions are only available so long as they won’t push a team over the “apron,” which is $6 million above the luxury tax. It would also create a hard-cap for the Raptors at the apron.

The Raptors would also have the minimum player salary exception, which allows you to exceed the cap to sign players on veteran minimum deals, so long as they haven’t triggered a hard cap.

Trade Exceptions

The Raptors have no meaningful available trade exceptions. They have one for $328,000 that expires on Feb. 23 and is more or less just a book-keeping note. They would lose this trade exception if they went under the cap, which would be a tragedy.

Assets

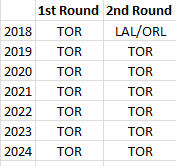

Picks

The Raptors own all of their own future first-round picks and all of their own second-round picks from 2019 onward. They do not own their own 2018 second-round pick, but will receive either the Magic’s or Lakers’ second-round pick that year, whichever is less valuable (the worse/lower pick).

Draft Rights

The Raptors own the draft rights to DeeAndre Hulett from back in 2000. Hulett was never anything more than a footnote – while these rights mean little, they also cost little, and in the event the Raptors wanted to acquire someone for nothing (think Luke Ridnour for Tomislav Zubcic in 2015), these rights can be used as “consideration” (both teams need to send something to the other in a deal).

The Raptors previously held the draft rights to DeAndre Daniels, too, but released him a few weeks back. There’s no reason for the move, necessarily, but it’s an act of good-will to the player (and agent) since the Raptors had no immediate plans for him.

Cash

The league allows teams to send out and receive up to $5.1 million in a season. This resets July 1, so the Raptors will have the full amount available to both send and receive.

Wrap

That’s a lot to sort through. The front office doesn’t have an easy job, and putting this together is a stressful endeavor because I know there are a handful of fans out there who will want even more detail/explanation and some who thought this was too in-depth for what a general fan needs. This is meant to be a pretty high-level preview of what the Raptors are working with entering the offseason (that is: not a complete scenario analysis), and I’ll do my best to keep updating with new posts as the team’s salary cap situation changes over the next few weeks.

The key points you need to know:

- There stands to be a fair amount of money chasing a good-not-great free agent class, creating some uncertainty. There are a few big dominoes that the league could pause waiting to fall into place, or there could be a frenzy after midnight on July 1 (though nothing can officially be completed until noon on July 6).

- The Raptors won’t have salary cap space unless they’re taking a major step back, but often teams are better off staying above the cap and using exceptions to fortify, anyway. It’s not ideal, but it’s workable. It means the Raptors are far more likely to be active retaining their own free agents or through trade than on the open market (think last summer).

- The Raptors can get creative by trading players away, so lot of additional scenarios are on the table in theory. They require homes for Carroll and/or Valanciunas, though, which may not be simple, and even then they wouldn’t figure to be a player for any major name.

- All of this adds up such that there’s really no means of replacing Lowry if he walks. They’d still have to renounce their other free agents to get into meaningful cap space, and it may not be enough to land a Jrue Holiday or George Hill, depending on how the market plays out. Trades exist, sure, but Lowry is a huge, huge domino for this offseason.

- I’ve written this a few times elsewhere, but a reminder: The sign-and-trade is not as common as it used to be. That’s because Lowry can’t get a single dollar more that way – your max in a sign-and-trade is the same as your max signing with a new team in free agency. Lowry would only be open to a sign-and-trade if it helped land him on a team that lacks the total cap space to sign him.

- Lowry’s maximum salaries: $149M on a four-year max from another team, $155.2M on a four-year max from the Raptors, and $201M on a five-year max from the Raptors.

If you have any questions, tweet them to me @BlakeMurphyODC or email them to me at eblakemurphy1@gmail.com, and I’ll do a follow-up post explaining certain rules or scenarios.