Extremely good or bad skill-sets in basketball are, much like the United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s definition of pornography, easy to recognize when you see them. It’s obvious simply with a quick gander that Kyle Lowry is good at shooting, or Ben Simmons bad at it. It’s plain as day that Pascal Siakam is a talented driver, or Danny Green a poor one. These elements of the game are worth mentioning, but only briefly, because they are self-evident. More words should be spilled instead on the basketball played within those poles. What of specific players’ skills that are neither obviously good or bad?

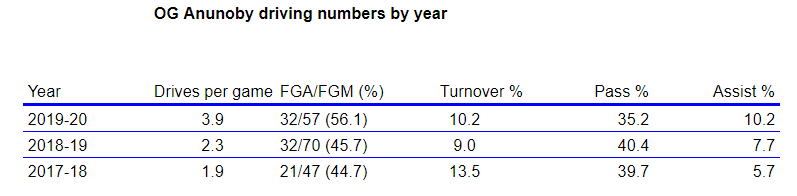

OG Anunoby is a massively improved offensive player this year. His defense, jump-shot, finishing – virtually every element of his game is both more effective and more consistent. Other than his defense, which is fantastic, he isn’t elite or horrible at anything. One element that will have outsized importance in determining Anunoby’s overall value as a player will be his driving game. To open the floor for his improved jumper, to keep him on the floor for his defense, to keep defenses honest for overplaying teammates like Kyle Lowry and Pascal Siakam: how Anunoby attacks the rim is a massive factor.

To that end, how has Anunoby been as a driver this year? To which extreme pole has he been closer?

The answer is not as simple as a simple good or great (though the most simple descriptor of his driving game would probably lie somewhere in between those two words). To evaluate Anunoby’s driving game, let’s break it down into five categories, starting at the rim itself and moving out: finishing, impact of contact, decision-making, handle and in-between game, and passing. Yes, this is the deepest of deep dives. Stay with me.

Finishing

Anunoby’s finishing is, on surface level, fantastic. Per Cleaning the Glass, he’s shooting 67 percent at the rim, which is 86th percentile for his position. He’s unbelievably strong and long, and those two things can combine into some incredible highlights.

He used to extend his off-leg like basketball’s version of a stiff arm, leading to lots of offensive fouls, but that is mostly excised from his game. Anunoby isn’t the most flexible, but he has good touch. His arm deceleration, allowing him to careen his body towards the rim at high speed, while slowing his release and leaving a soft layup on the backboard, isn’t great, and he prefers to slow down his entire body so that his release is at the correct speed. Because he’s still so strong, that doesn’t seem to hamper his finishing ability.

When he can’t jump over or through the defense, he’s solid at using his body to shield the ball from the defender.

And as probably the newest element of his finishing game, he’s developing solid counters. He has a solid, if slow-motion, spin move, and he has a good euro-step to get to his inside foot. His counters may be unplanned, but they’re unexpected as a result. They look counter-intuitive, but they yield results.

Though Anunoby is capable of being an exceptionally strong finisher, it doesn’t always turn out that way. He can lose focus and blow easy ones, and he can occasionally show a strange passivity around the rim. Aggression is hard, and constant aggression is even harder. It’s part of what separates the best players in the world. And it’s obvious when Anunoby’s aggression wavers.

On the plus side, Anunoby is practically an ambidextrous finisher. He has deft touch with his left hand, and he doesn’t lose that ability when he’s on the move or hanging in the air. He does a good job of setting up his left hand to keep the ball away from the contest, whether he jumps off his left or right foot.

Speaking about his feet, Anunoby is a fantastic left-foot jumper and a quite good leaper off his right. Some of these clips are included elsewhere, but watch his feet. He’s very natural getting onto his left foot, and he gets ridiculous lift when given a runway.

Anunoby is not as fantastic a leaper off his wrong foot, but he uses wrong-footed finishes smartly, and his movements are becoming more fluid going the other direction. It’s a work in progress, and it can look choppy, but the results are still solid.

It’s not even worth mentioning Anunoby’s two-foot jump. At least as a driver, it’s not something he uses, and he doesn’t get great lift.

Another downside: he often doesn’t use all the steps allotted to him. He doesn’t chop his strides well, and his center of balance can end up too far away from a natural release point for him to take a final step. He can get lost in his own steps, and he sometimes doesn’t end up where he wants to go.

All of this adds up to Anunoby being a very good finisher. When he does actually release his shot, he is excellent at putting it in the basket. But a lot of the side skills that set up a player getting off his shot, like his stride, aren’t at an equal level yet. That’s why Anunoby has elite finishing numbers, at, to repeat, 67 percent around the rim, yet he only averages 1.7 shots out of drives per game. In general, the side skills add to quantity, and the actual finishing skills add to quality. Let’s move further away from the basket and see how Anunoby is at setting up his finishes.

Impact of contact

Contact is one of the most important elements of finishing in the NBA. It’s a seemingly uncontrollable aspect of a game, as offensive players can’t completely eliminate defensive efforts. Still, the best finishers in the NBA, like LeBron James of yesteryear, or Giannis Antetokounmpo of today, are almost unbothered by contact. That’s not because those finishers are so strong that contact doesn’t matter, although that’s part of it. They are unbothered by contact because the best determine when it takes place, on the ground instead of in the air, and early during a shot attempt instead of late. Then when things go wrong, strength plays a huge part, and the best can power through unwanted contact.

Anunoby is a fantastic finisher when defenders chase the ball rather than his body. He has great balance, and he hangs in the air. If the contact comes early or not at all, the basket is basically a forgone conclusion.

Anunoby can mistime that contact. He loses his strength entirely if the contact comes in the air, and his finishing becomes more of a crapshoot fling-it-at-the-rim-and-hope than a smooth layup attempt.

One problem is that Anunoby clearly knows that he’s supposed to create contact early, on the ground rather than in the air. That can create issues where Anunoby is too physical seeking defenders’ bodies, and he is whistled for a lot of offensive fouls. These aren’t accidental collisions, but instead intentional ways of creating contact early before he leaves his feet. Anunoby needs to get better at making such plays less overt and less physical.

When Anunoby expects contact and doesn’t receive it, his balance can be thrown entirely out of whack.

Anunoby is occasionally great at finishing through contact. When he does draw a foul, he converts the and-one at a rate of 36.4 percent, which is 88th percentile in the league. However, he isn’t fantastic at actually drawing a foul, as he only draws shooting fouls on 7.3 percent of shots, which is 37th percentile. This yields basically the same conclusion as the finishing element of Anunoby’s game; his quality is high, but his quantity is low. Anunoby needs to improve the surrounding skills to add consistency and frequency to his finishing game. One major element of that is improving at his ability to create contact at the correct time and place and then finish through it.

Decision-making

This is where we come to some of the lesser developed elements of Anunoby’s driving game. Some decisions are impossible to know without being Anunoby himself. Others are knowable purely because of the result; we know Anunoby did not make the correct decision because of a blatant offensive foul, for example. But to be a good driver, one has to make rapid-fire decisions at each level of defensive attention. The best drivers read the defense three times or more on a single drive: once on the perimeter, usually while veering around a screen, a second time when digs and stunts flood into line of sight, and a final time when reaching the paint and facing one or more contests. Those drivers change pace, direction, angle, and more to confuse the defense and make sure defenders are a step behind the drive. Anunoby doesn’t have any of those multi-tiered drives from which to draw. The best example of multiple correct decisions strung together in short succession is a buttery post-up against the Washington Wizards, which isn’t really a drive, but is a good example of quick-trigger multi-tiered decision-making (wow that sounds like buzzwordy corporate jargon).

More frequent examples, unfortunately, abound of Anunoby failing to adapt to changes in the defense. When one aspect of a defense differs from the norm — say a defender stays in the lane after a cutter clears — Anunoby can have trouble digesting that information and changing his plan. At other times he doesn’t, or can’t, change his angle of attack when defenders are clearly in perfect defensive positioning. These result in charges, travels, or badly missed shots.

Better decision-making comes with reps. And for a non-guard who drives only a small handful of times per game, and then usually against rotations or other weakened defensive structures, those high-level reps are very hard to acquire. After Anunoby’s post-up against Washington clipped above, I asked Nick Nurse about how the Raptors go about adding balance and fluid motion to Anunoby’s driving game. It’s not as obvious as adding a jump-shot. Nurse gave a great answer about how they work on it with purpose.

“Mostly through reps, right? I think that’s probably one of those things that at some of those plays that he just needs to get some more reps for balance,” said Nurse. “You see some of the ones where he goes in there and just doesn’t quite get to his base, right, or gets off stride or something. I think that you either got to get two feet so you get on balance, or you have to go real slow in that Euro and stay on balance as you’re going from one foot to the other. He works on it, though. I think everyone can see the improvement. We saw a couple of little bit off-balance drives from him tonight but over the course of the last four, five games, we’ve seen a lot of really good straight line drive finishes from him on each side of the basket.”

Handle and in-between game

Anunoby’s dribbling skills are probably the least advanced component of his driving game. He has very few baskets made after breaking down a set defense, and the vast majority of his drives come when the defense is in rotation and the lane is open. In other words, Anunoby usually drives only when he doesn’t need to dribble to get to the rim.

One element of his game that shows his dribbling inconsistency is Anunoby’s predilection to lose the ball to a swipe, either from a digging help defender or a beaten primary defender. His handle can be quite loose.

Digs especially bother him. We talked earlier about three tiers of decision-making, on the perimeter, during the drive, and at the rim. Anunoby’s decision-making in that second stage before he’s actually in the process of shooting, but with multiple bodies around him, could use work.

Part of what limits Anunoby’s decision-making during the drive is his lack of in-between game. He has no floater or pull-up to speak of. On the year, he’s shooting four-of-16 from short midrange and three-of-eight from long midrange. There is basically no threat Anunoby offers, while driving towards the rim, other than reaching the rim and trying to dunk over or finish around a contest.

The of diversity of his driving offense is part of what limits the frequency of his driving game. He can only really score if he makes it all the way to the rim, and because he lacks a high-level handle, he can’t often get all the way to the rim some element of the team’s offensive strucutre helps him get there. Anunoby is solid at grabbing his own miss and putting it back in, scoring 1.35 points per putback possession, but that doesn’t add enough value. Adding a nuanced in-between game — say, a floater or push shot, a pull-up jumper, a few more dribbling moves, and a tighter handle and gather — would skyrocket Anunoby’s ability to get to the rim and finish when he’s there.

Passing

One element of Anunoby’s game that is actually underrated is his ability as a passer. He came into the league with surprisingly deft vision and touch as a passer. Though that element of his game was placed on the back-burners for a few seasons, Anunoby has unleashed it here and there this season. He’s best at hitting a cutter either on the dunker spot or at the free throw line.

Anunoby hasn’t done it a lot this season, but he has some glimpses of skill at hitting shooters, as well. Because he’s such a dangerous finisher, he often draws multiple defenders. He may not be able to juke multiple opponents out of his way or bulldoze them, yet, but he can still kick the ball to waiting shooters who were abandoned by the defense. One cross-court pass in transition stood out, especially, as perhaps the best pass of his NBA career.

There are some limitations to Anunoby’s passing game. Aside from not being a high-frequency event, Anunoby often sees passing lanes after they already close. He lacks the elite feel and grasp of angles to pass it over or through multiple defenders.

Because Anunoby’s decision-making doesn’t always happen a step ahead the defense, he can turn it over looking to kick the ball out to shooters, especially if the defense doesn’t contract much on top of his drive. Long defenders can bother his vision.

Because of the way Anunoby’s game and body are structured, passing for assists will never be the primary purpose of an Anunoby drive. He is driving to score, which is something that he’s already quite good at. Still, passing can open the floor for himself and his teammates. Without an elite handle, passing is another way to beat defenses when they dig deep into his drives. His decisions can sometimes come too late to keep an advantage alive, but he has shown enough of an aptitude to make it a weapon. Like every other element of his driving game, consistency is the next step for Anunoby’s passing while on the move.

Conclusion

Does knowing all of this leave us anywhere that’s different from where we started? One would hope.

Perhaps most importantly, the fundamentals are there. Anunoby is extremely long and strong, with great vertical burst, and that’s enough to be one of the better finishers in the league. Again, his league-wide percentile as a finisher around the rim is 86th. That speaks volumes.

Secondly, Anunoby is still improving. A number of the skill developments of the past few years, such as his counters, the deftness of his left hand, his cross-court passing, and more, are relatively new. In fact, the entire concept of his driving game is a work in progress.

Anunoby’s driving numbers this year are most similar — in terms of number of drives per game and shooting percentage when driving — to non-star players, as far as forwards go, like Evan Turner, Kent Bazemore, or Thaddeus Young. Anunoby shoots a high percentage, but he’s far outside of the category, in terms of adding high quantity and maintaining quality, of even secondary scoring wings like Evan Fournier, Tobias Harris, Jeremy Lamb, or Khris Middleton. The point is that Anunoby still has a long ways to go.

There are, of course, a variety of pieces of Anunoby’s driving game that need work. His handle, aggression, ability to manipulate contact, speed of decision-making, and ability to recognize passing lanes early are all factors that worsen, in order, his frequency of attempts at the rim, turnover rate, and finishing ability. Those are all fixable weaknesses. Anunoby has clearly been working on a variety of these elements; he will, sometimes over-zealously, intentionally initiate contact on the ground. Over his career, Anunoby has gotten better at many of these skills, and he will continue to improve.

So how to evaluate Anunoby as a driver? He’s both low-quantity and high-quality. He has a long way to go, but his statistical profile is similar to some young wings who eventually became stars. Think guys like Jimmy Butler, Kawhi Leonard, or Pascal Siakam, who were fantastic drivers in low minutes and low attempts and then carried that great ability into higher usage as their careers and skills progressed. Now, Anunoby doesn’t have the foundation, especially in the dribbling and decision-making departments, of those players. Plus, they all became all-NBA wings. But, per Cleaning the Glass, Anunoby does have relatively similar frequency and accuracy rates at the rim to each of Butler, Leonard, and Siakam in their third seasons. Anunoby’s game doesn’t look as fluid or as natural as any of those superstars, even when they were in their third years, but Anunoby’s numbers still show great success.

That’s the most important fact. Anunoby is fantastic as a finisher. There are a huge number of skills that could improve his ability to get to the rim. He’s already good, though. If he gets better at all of those skills together, he’s looking at an all-NBA career. That’s optimistic, but it’s a possibility. And if it happens, us knowing what we’re looking at won’t be the only thing Anunoby’s driving game shares with pornography.