Most of the time, when a team tries to score the basketball in the NBA, it’s going to look the same as when another team tries to. Every team initiates out of pistol and horns and other variations of ways to start sets with players in certain locations of the floor. Every team has shooters spacing the floor and timed cuts from the baseline and the 45-degree angle. But most of all, every team runs an absolute meat grinder’s worth of pick and rolls during a basketball game.

Over and over, on nearly every half-court possession, someone dribbles the ball beyond or near the 3-point line while another player ambles over and stands near the dribbler’s defender. Then the dribbler attacks, dribbling either towards the screen or away from it, asking his defender to either run into the screen or dodge it. And the offense balloons out from there, with branching tree paths. But the beginning is almost always the same.

According to Second Spectrum, no NBA team ran fewer than 54 picks per game last season. Some ran more than 80. On average last year, for any given offense last year, there were just over 80 halfcourt possessions per game and just under 70 picks per game. So, yeah: The play happened a lot.

Yet the Toronto Raptors no longer employ the player who ran the bulk of their pick and rolls. Fred VanVleet ran the most pick and rolls for Toronto, and while he wasn’t one of the most efficient purveyors of the play, he was one of its most frequent. VanVleet ran 2113 pick and rolls last year, just over 40 per 100 possessions, which ranked within the top 20 last year. The next most frequent pick-and-roll handler was Pascal Siakam, coming in at 83rd in frequency, running just over 20 picks per 100 possessions. So someone has to take those possessions that VanVleet is vacating.

The most obvious option would be Dennis Schroder, signed mere moments to the Raptors after VanVleet took his talents to Houston. Fresh off of dominating international games for Germany — including against Canada — Schroder is a skilled veteran.

But last year, his efficiency in the play was lower than VanVleet’s — 0.952 points per chance compared to VanVleet’s 0.968 — despite playing alongside more shooting and a truly elite roll big in Anthony Davis. (VanVleet’s efficiency with Jakob Poeltl, 1.080 points per chance, was higher than Schroder managed with Davis or with LeBron James as his rollers, per Second Spectrum.)

And Schroder’s tendencies in the pick and roll will probably limit him further than they did in Los Angeles. He was not an elite self-creator, with almost three times as many passes out of the pick and roll as shots, per Second Spectrum. And his efficiency when shooting out of the pick and roll was a lowly 0.896 points per chance. VanVleet was closer to a 2:1 pass-to-shoot ratio (the best pick-and-roll operators functioned within this same range) while being more efficient when shooting than passing. His 0.990 points per chance when shooting out of the pick and roll dwarfed Schroder’s. VanVleet attempted pull-up triples out of the pick and roll at a frequency of more than six times Schroder’s (17.768 per 100 possessions versus 4.360), and he was significantly more efficient there, too. Schroder shot 24.2 percent on pull-up triples last year and has only two seasons in his career above 30 percent on such shots.

When Schroder did score out of the pick and roll, it generally came via shots in the midrange, where he was more efficient than VanVleet — particularly in the short midrange, where VanVleet was one of the least accurate players in the league. Schroder has a bag of tricks in that area, but the biggest improvement on VanVleet will be with the floater. Among players with at least 50 floaters attempted, VanVleet had the worst efficiency in the league, per Second Spectrum. Schroder was right around average — a big improvement — and he has great, tight handles to get to the shot at will or his counters if bigs overplay the floater.

However, it will be difficult for Toronto to manufacture space in those areas for Schroder. In Los Angeles, Schroder was much more efficient when shooting out of the pick and roll with Davis playing center and James off the court. Los Angeles had more spacing, particularly after the trade deadline, with D’Angelo Russell, Austin Reaves, Malik Beasley, Troy Brown, and other shooters able to flank Schroder. Those lineups — with Schroder and Davis on and James off — were behemoths for the Lakers, outscoring opponents by 7.4 points per 100 possessions.

The Raptors can perhaps simulate those lineups, with Schroder and Poeltl on the court, but it is hard to get enough shooting around them. O.G. Anunoby would be a great fit, but neither Pascal Siakam nor Scottie Barnes would help the spacing. In last year’s games in which both players were available, Toronto played only 239 minutes with both Siakam and Barnes on the bench versus 3045 with one or both playing; Schroder-and-Poeltl plus shooters is not really going to happen very often.

Schroder will run plenty of pick and rolls for Toronto, but unless he reorients his preferences or Toronto rejigs its roster construction, it’s unlikely that Toronto’s half-court offense will improve with Schroder running the show.

He’s far from the only option, of course.

Siakam last season was one of Toronto’s most efficient pick-and-roll handlers, coming in just ahead of VanVleet’s 0.968 points per chance with 0.972 points per chance of his own, according to Second Spectrum. Siakam was Toronto’s best player by a wide margin last season, and his superiority extended to virtually every aspect of the offense. However, his second-most common pick and roll partner was VanVleet himself, and Siakam was significantly more efficient running picks with VanVleet as the screener (0.980 points per chance) than a traditional big like Poeltl (0.855). Like Schroder, Siakam rarely pulled up from deep when opponents went under his picks, and when he did he was very inefficient (27.4-percent accuracy on pull-up triples).

Siakam was at his best with a shooter screening for him — whether VanVleet, Gary Trent jr., O.G. Anunoby, or even Chris Boucher. If he used that space to pivot into a drive (1.058 points per chance after a pick) or a post up (1.412), he was one of the best in the league. Siakam is a gifted mover, with elite body control and touch. He has great patience, turning cut-offs into advantages by reorienting his drive and taking his time. He may not be able to replace VanVleet’s quick-score pull ups out of the pick and roll, but Toronto should be able to buy Siakam more space than it will Schroder. (Largely because putting Siakam on the ball means his not being off the ball disallows an extra defender from sinking into the paint to gum up the works.)

If Toronto can maximize spacing with the ball in Siakam’s hands — say, alongside Trent, Anunoby, Gradey Dick, and Otto Porter jr. — it’s hard to see a defense consistently stopping Siakam-run pick and rolls. His usage in the play ought to creep upwards. However, he was miserable when running picks with Poeltl or Scottie Barnes as his screener, so roster construction could limit the frequency with which Siakam is handling the ball, too. He scored 1.084 points per chance in the pick and roll with both Poeltl and Barnes on the bench, which would have been a top-20 mark last year, comparable to Jamal Murray or Kyrie Irving in the pick and roll. (Barnes, on the other hand, scored 0.909 points per chance with Poeltl and Siakam on the bench. No one on the Raptors was good in that situation.) Siakam, in every way, was a requirement for offensive success last year for Toronto.

Again, though: It will be hard for the Raptors to find big minutes for Siakam without a cramped court. Barnes and Poeltl are and should be mainstays, as they are exceptional at so, so much of the game outside of shooting. It might optimize Siakam-run pick and rolls to keep them off the court, but it would sacrifice so much else for the Raptors.

Perhaps the fan favourite option for running pick and rolls would be Barnes. He is the heir apparent for the Raptors, and because he’s such a genius passer, there’s inherent logic to asking him to run the point guard position. (Even if he hasn’t been good at it yet.)

Yet Barnes’ 0.916 points per chance in the pick and roll last year was far below average, and his only really effective partnerships were with Siakam as the screener (1.193 points per chance), Christian Koloko (1.087), or VanVleet (1.020).

What held him back — on top of, like everyone else on the Raptors, not being a pull-up shooter (21.4 percent accuracy) — was that Barnes was rarely able to get his hips past his primary defender in the pick and roll. His lack of functional handle or quickness meant instead of straight-line drives, he was at his best using syncopated, bully-ball drives to incrementally move towards the rim. That can work, but it takes a long time, allows defenders extra time to swarm the paint, and it doesn’t create the highest-value looks at the rim. The best pick-and-roll handlers are much more fluid movers than Barnes, and he takes a long time to eat space. When it works, it’s generally because he converts a moderately difficult look.

Barnes is, without a doubt, the best passer on the Raptors. But he isn’t often able to manifest that passing when he’s the one initiating the play. He isn’t as often able to reach the rim to unlock his brilliant finishing. Toronto would be best served using him in more dynamic ways than simply initiating plays. He could be the screener, for example, where he could catch the ball closer to the rim to force rotations and unlock his passing. He could be used off the ball, and if his defender sinks to the paint, that could trigger an immediate swing or get action for a handoff against a now-out-of-position big defender.

That didn’t happen, per say, last year, but the Raptors always got great looks when Barnes was the second-side handoff setter. He can’t do as much of this if he’s the initiator. (And the Raptors should do much, much more of this.)

If such moments have more scripted triggers, with more certain spacing, Toronto could build a lot out of such actions. There are lots of options for Barnes to contribute outside of initiation, and Barnes is so excellent that he’ll find ways to contribute positively in a variety of situations. Despite his initiating troubles last year, his offensive on/offs were hugely positive, at plus-2.6 points per 100 possessions. (When he was the functional point guard, with VanVleet off the floor, Toronto’s offense rating was a miserable 111.0 points per 100 possessions, much lower than its season average of 115.9.) Barnes will certainly see more pick-and-roll reps next season than he did in 2022-23. But unless he has functionally improved several elements of his game, it’s hard to see a successful offense with Barnes leading it; instead, it’s much easier to envision success with him as a second-side trigger in more dynamic actions.

Toronto’s last option to run a boatload of pick and rolls next year is its likely (and nominal) starter at the point guard spot: Gary Trent jr. On one hand, it doesn’t make sense to ask a player who’s never averaged more than 2.0 assists per game to run the offense. But at the same time, Trent is Toronto’s only threatening pull-up shooter. (Although he shot 29.9 percent on pull-up triples last year, he has spent the rest of his career above league average on such shots.) At the very least, Trent can force rotations at the point of attack simply by holding the ball in an area from which he can score.

Yet Trent is not a willing or capable passer when he does force those rotations. He wants to shoot, and even if he does draw the defense, he hasn’t shown he’s able to punish opponents by making an immediate read to keep the play moving. Of the 91 Trent-run pick and rolls on which he passed that ended in a make, per Second Spectrum, only 13 of those baskets resulted in assists for Trent. That percentage of 14.3 percent paled in comparison to Siakam’s 51-of-204 (25 percent), for example. He simply didn’t capitalize on advantages to the extent that other Raptors do. If he doesn’t score, such plays generally result in no advantages, a reset, and a new play.

Toronto managed only 0.925 points per chance on a Trent-run pick and roll. Trent is elite as a second-side handoff option (especially with Barnes!), but he will likely not add a huge number of picks to his plate. He ran 496 last year, and I would doubt that leaps beyond 700 or 800.

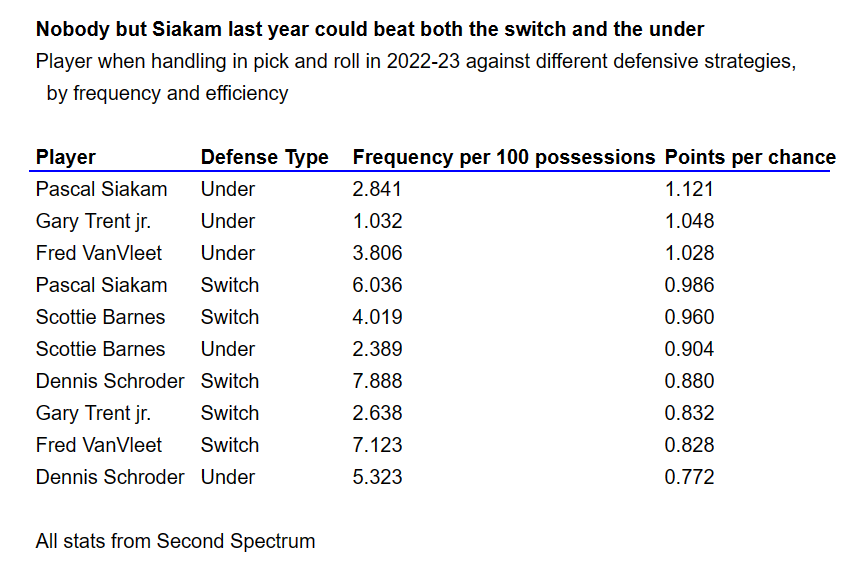

This discussion of the limitations of Schroder, Siakam, Barnes, and Trent should beg a question: What will Toronto do when opponents go under or switch picks? Last year, Toronto was the second-least efficient team in the league at scoring against switches, scraping its way to 0.905 points per chance, per Second Spectrum. It was slightly above average when the ballhandler went under, which is somewhat surprising. But plenty of Raptors were successful, there; only Siakam was above average in both circumstances.

Siakam is more or less Toronto’s only hope to obliterate opposing defenses when they play conservative, intact-shell schemes like under or switch. He’s the only player Toronto rosters capable of defeating both schemes. And VanVleet’s inability to beat even a lumbering big like Nikola Vucevic in a switch was perhaps the second-most significant reason the Raptors lost their play-in game last season. Siakam doesn’t have that trouble.

Siakam ate unders last season, attacking lead feet, trusting his jumper without defensive attention, and using all the time allotted to him. He scored a ridiculous 1.241 points per chance on shooting possessions used after opposing guards ducked under a pick.

When opponents switched, Siakam was more judicious, doing his damage instead more with the pass. His patience and movement were fantastic at creating open space for teammates.

Only 13 other players faced at least 150 picks with defenders going under and 150 picks with defenders switching while scoring as or more efficiently than Siakam in both circumstances, and the list is a relative who’s who of stars: Steph Curry, Luka Doncic, James Harden, De’Aaron Fox, DeMar DeRozan, Russell Westbrook, Anthony Edwards, Chris Paul, Monte Morris (!), Tyrese Haliburton, Davion Mitchell (!!), Jordan Poole, and Darius Garland. That’s good company, and it means that as long as Siakam has a synergistic screening partner, there’s no coverage that can limit him in the pick and roll.

That’s good because if Toronto is going to be successful in the half court next season, it will need its players to succeed in the pick and roll. And it can’t be just one; no one player will add the 2113 picks to his plate that VanVleet organized last season. (Not to mention the 254 on-ball screens and 488 off-ball screens that he set.) As far as lead guards go, VanVleet was below average on efficiency when it came to running pick and rolls, although that improved once he began to run the play with Poeltl as his screener. But Toronto needs to portion out VanVleet’s totality of responsibility while also hoping to ensure its efficiency in such a vital play improves.

Siakam can add a few hundred more picks to his plate and score more efficiently than VanVleet did. Schroder will eat perhaps 1500 picks (he ran 1687 last year), and in the right circumstances (with a big as his screener and shooting across the rest of the lineup), he can score as or more efficiently than VanVleet. Barnes and Trent will take a few hundred more of their own. But Toronto will have a balancing act to accomplish. Some picks will need shooters as screeners. Some will need bigs as screeners. Darko Rajakovic will need to pull the right levers, as Toronto’s lineups and entire rotation will need to be dynamic and agile in order to ensure success for different players with such different requirements.

But the entire NBA is improving, and fast. Last year saw the highest average offensive rating in history, at 114.8. Toronto in fact set its franchise offensive rating record, at 115.5. Even though the Raptors saw a raw jump by more than 2.0 points in offensive rating from the year prior, the team was relatively worse compared to the average offense. As NBA offense is accelerating into the stratosphere and beyond, Toronto can’t stagnate; it must improve in order to keep pace. Much will need to change on offense. But who runs pick and rolls, and how, will go a long way to determining where Toronto finishes on the offensive food chain.