Why aren’t there OVO masks yet?

The Big Question for Sports: When Will You Feel Safe Around 20,000 Strangers Again? – WSJ

But the primary challenge for the business is not a political or financial one. It’s behavioral.

“The overall biggest long-term problem for sports is the fear associated with public interaction,” Golden State Warriors owner Joe Lacob said in an email. “When does that go away? When will society decide that it is once again safe to interact in public? That is the big question for sports teams and leagues.”

“The good news is that this virus will be beat and things will return to normal,” he wrote. “We know the enemy, and medical knowledge and capabilities are greater than ever in history.”

How long that will take is a question that no one in sports is qualified to answer—and epidemiologists, immunologists and infectious disease experts are still trying to wrap their minds around.

What they do understand, as the year slips away, is that how sports fans behave mirrors the behavior of large groups in society as a whole. Even if people were allowed into offices tomorrow, it’s uncertain when they would have the appetite to surround themselves with anywhere between 20,000 and 100,000 other fans at stadiums.

Some leagues, governing bodies and even the International Olympic Committee have stopped trying to predict the future. The Olympics were postponed until next summer. Wimbledon will skip 2020. Belgium’s top soccer league simply declared a champion last week. The only thing for the rest to do is search for alternative dates and keep waiting.

The NBA is exploring the concept of hosting the playoffs in a fan-free bubble if they get clearance from public health officials, while the English Premier League is contemplating a shift for the last quarter of its season to the middle of summer. But there are many skeptics in the NBA, including LeBron James, and the most ruthless soccer league on earth acknowledges that matches will be on hold until the conditions are “safe and appropriate.”

Even if they manage to finish this season, they could find themselves in the same position next season. They could also find themselves running into ferocious competition for eyeballs with the NFL and college football—if those seasons begin on time. California Gov. Gavin Newsom said on Saturday that he doesn’t believe his state’s three NFL teams will be playing in front of fans come September.

Amy Huchthausen, commissioner of America East Conference, said that she’s already noted small shifts in her own life that foreshadow larger ones in society. She notices the nearest person on the sidewalk when she’s outside now. That sense of heightened attention figures to be common in crowded stadiums.

“I think we’re naive to think that’s not going to persist in a long-term way even when we’re past the virus and past the pandemic,” she said. “I have a hard time believing that once an order is lifted, people are just going to flock to go back to a 50,000-seat or 100,000-seat stadium like they did before.”

That would render plans for near-term comebacks as useless as a face mask made of tissue paper. The basketball and soccer leagues in China, where the virus appeared to be dissipating under strict controls, hoped to return to action this month in empty venues. They quickly abandoned those hopes. South Korea canceled the rest of its basketball season. Japan has postponed baseball’s opening day—twice.

Giannis Antetokounmpo is spending much of his time during the coronavirus-imposed hiatus working out, helping care for his newborn son and occasionally playing video games.

What the reigning MVP isn’t doing very often is shooting baskets since the NBA has closed team practice facilities.

“I don’t have access to a hoop,” the Milwaukee Bucks forward said Friday during a conference call. “A lot of NBA players might have a court in their house or something, I don’t know, but now I just get my home workouts, (go) on the bike, treadmill, lift weights, stay sharp that way.”

The hiatus is forcing thousands of athletes, pro and otherwise, to work out from home as they try to keep in shape. Equipment varies from player to player, too.

“It all comes down to what they have and what they’re capable of doing,” Atlanta Hawks coach Lloyd Pierce said. “We can do a lot of body weight stuff. That’s how they stay ready. That’s the most I can offer as a coach for them to stay ready. I can’t say, ‘Hey, can you find access to a gym?’ That would be bad management on my part.”

For instance, Pierce said Hawks guard Kevin Huerter has access to a gym in New York and guard Jeff Teague owns a gym in Indiana.

Other players face different situations.

“I’ve seen LeBron’s Instagram,” Pierce said of Los Angeles Lakers superstar LeBron James. “LeBron has a house with a full weight room and he has an outdoor court. He’s got a different reality right now that gives him a little more access to continue the normal. (Hawks rookie) Cam Reddish lives in an apartment and it’s probably a two-bedroom apartment. He can’t go in the apartment weight room because it’s a public facility. So he’s limited in all things.”

NBA Offensive Styles: What data tells us about perceived changes to the game – The Athletic

As a quick aside, while the proliferation of shot charts has helped digestion of the game in some ways, it has possibly hindered in others. Much as a simple categorization and collation of current playing styles is merely a stationary snapshot in time rather than the full picture of where the game has come from on its way to whatever is next, shot location is simply a static endpoint of a possession. As we’ve learned using all the tools and additional information provided from tracking data and other sources, where a shot took place on the court barely begins to describe that shot. Was the shooter moving and if so how fast and in what direction relative to the hoop? Was he closely defended? Did he dribble before he shot? How long did he have the ball before shooting? How much time was remaining on the shot or game clock? The answer to all these questions and more have a tremendous impact on how likely a shot is to be made, in many cases to a larger degree than simply noting the location of the shot.

So to simply aggregate shot locations for a team and player and say that adequately describes offensive style is missing all of those things that constitute style. Additionally, shot location doesn’t capture what happens on the other 20 to 25 percent of offensive chances, those that don’t end in field goal attempts, instead resulting in free throws or turnovers.

Instead of looking at shots, what if we considered the actions that lead into this whole array of offensive outcomes? Which brings me back to play typology and our second-best data set: Synergy. Though the vagaries of manual play coding and tracking and how the standards for doing said charting have changed over time make Synergy data very risky to use in terms of building robust evaluative or predictive models, I feel confident enough in the broad accuracy of the data to use it descriptively to catalog the evolution of style being discussed here. Though the data from earlier seasons is only partial, we have information from at least 75 percent of games going back to the 2004-05 season — the 2004-04 season covers 70+ games for most teams while subsequent years have data for 90 percent and upwards of games logged — which unlike tracking data does capture the bulk of the stylistic revolution in NBA play.

The unknown path to the Tokyo Olympics begins anew for the Canadian men’s basketball team this week, with far more questions than answers.

A conference call is expected soon, bringing together administrators, coaches and players to at least provide updates on an uncertain future.

“Just to touch base and keep some connection and keep people together a little bit,” Nick Nurse, head coach of the Raptors and the Canadian team, said on his own conference call last week. “Also conveying those same messages (he delivers to the Raptors): to stay healthy and stay fit as best you can, and when the time is right we’ll get back to work and reconvene.”

Nurse remains steadfast in pursuit of Canada’s first Olympic berth in men’s basketball in more than 20 years, but an assistant coach on his Raptors staff is mulling his international future.

Sergio Scariolo — who coached Spain to the 2019 FIBA World Cup gold medal, bronze at the 2016 Rio Olympics and Olympic silver in London in 2012 — is weighing whether or not to remain on the job with the national team. He was under contract through the 2020 Olympics but now is considering an extension through 2024, after the Tokyo Games were postponed a year.

“If it were up to me, I’d be happy to continue,” he said in a Twitter conversation with Spanish journalists on Friday, according to the translated version on Eurohoops.net. “But we have to reflect with the family. The family is what I have sacrificed the most for many years, for being so little at home. And I also have to come to an agreement with the Raptors.”

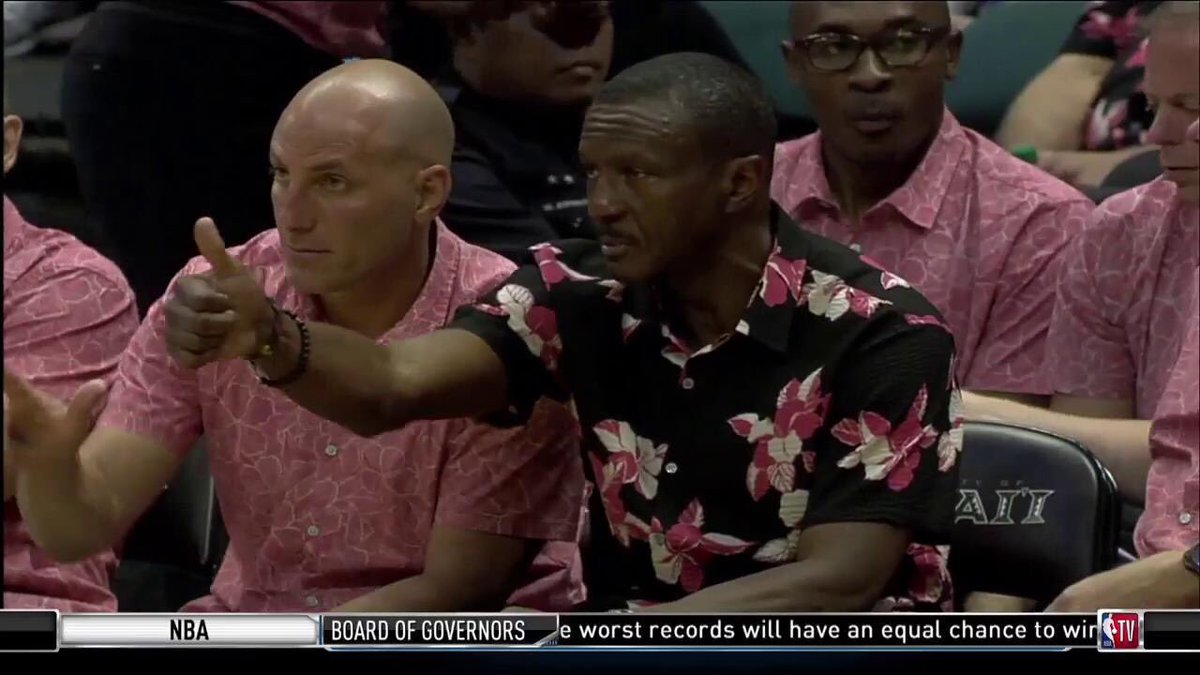

Raptors’ 25-year Retrospective: The Casey Years | Toronto Sun

“I think everybody thought I would be, ‘Woe is me.’ But I looked at it the other way,” Casey said in an interview with Michael Lee of The Athletic. “What it did, it reinforced what I was I doing. And that group took it over the hump and finished it.

“I was happy for the players, for the country and the team. It really energized me, that what we were doing was right. I took that from it, more than jealousy.”

And how could he not? Casey was the man behind the bench when this thing finally started heading in the right direction.

Casey arrived in Toronto in 2011 fresh off a championship with Dallas. He was one of Rick Carlisle’s lead assistants on that Mavericks team and his handling of the defence earned him plenty of praise and an opportunity north of the border.

So it was not a surprise at all when he arrived in Toronto in the summer of 2011 and immediately went to work on the Raptors’ porous defence.

The team only improved by a win over the previous year in a lockout-shortened season but the Raptors’ attitude towards defence changed dramatically.

In one year with Casey at the helm the team went from the worst defensive rating in the entire league (112.9 points allowed per 100 possessions) to 14th as the new coach’s focus on defence chopped a full 81/2 points per 100 possessions off that disappointing mark. Casey’s dedication to defence remained front and centre throughout his tenure.

Casey’s Raptors weren’t just more defensively responsible, year by year they grew into a team others hated to face because of the physical nature of that defence.

Though each of the major leagues has endured multiple seasons affected and shortened by labor disputes, it was work stoppages that caused the lone two instances of a “no champion” designation in the history books: MLB in 1994 and the NHL 11 years later.

In 1994, there was no World Series because of a players’ strike that began Aug. 12 of that year and was left unresolved until well into 1995.

Similarly, there were no Stanley Cup playoffs in 2005. They were called off by commissioner Gary Bettman on Feb. 16. The 2004-05 NHL season never got started because of a lockout that began Sept. 16, 2004.

Citing aggregate losses of $273 million two seasons prior, NHL owners dug in on a demand for a leaguewide salary cap. Through NHLPA executive director Bob Goodenow, players vowed to never accept one.

That left for an impasse, and not even an imposed deadline could break the stalemate. The league and union ramped up negotiations in January 2005, but the “philosophical differences” proved too much to overcome.

Even though the Players Association ultimately relented on the issue of the salary cap, the haggling over the precise figure to set it at dragged on too late for what Bettman believed could be a representative season. So, on a winter Wednesday afternoon in Manhattan he announced the first cancelation of a full major North American sports league’s season in history.

“This is a sad, regrettable day that all of us wish could have been avoided,” Bettman said.

The league and its players came to an agreement in July 2005 — the hard salary cap a central tenet of it — and the Stanley Cup has been safe since.

The summer of 1994 similarly featured simmering tensions between MLB players and owners that culminated when players began a strike on a day they had long warned was their deadline for doing so.

Like hockey owners a decade later, baseball team owners had offered several proposals to the MLBPA that featured salary caps. The players wanted no part of a cap — unlike their hockey brethren, though, they never buckled.

While suggestions such as a September Stanley Cup and a Christmas World Series are given credence, Sept. 14 was a curious drop-dead date for the 1994 MLB season.

“There’s an incredible amount of sadness,” Selig said that day in canceling the World Series. “It is very hard as I told the group on the phone to articulate the poignancy of this moment. There is a failure of so much.”

“That’s ultimately what everyone wants to see,” Leonard said of the postseason. “That’s why players play, they play for a championship. … And so, I would think we would need at least five games or so to get our legs underneath us and then, boom, right into the playoffs and figure out who’s the champ.”

At present, the Heat (41-24) would be the No. 4 seed in the Eastern Conference and would face the Indiana Pacers in a first-round series. Just two games separate the Heat from the Pacers and Philadelphia 76ers.

Some teams may balk at such a short regular season upon resumption of basketball, however. The Washington Wizards (24-40), for instance, sit 5.5 games back of the Orlando Magic for the No. 8 spot in the East. Catching them with the 18 games the Wizards have left on their schedule would be a tall task, no doubt, but possible. Catching them with a regular season shortened to five games would obviously be mathematically impossible.

Granted, it remains unclear if the 2019-20 season will resume at all amid the coronavirus pandemic, so all options remain on the table, from pushing the league calendar back into the late summer and perhaps even autumn to canceling some or all remaining regular-season games.

Soccer’s Coming Storm – The New York Times

At first glance, the problem is clear, and the problem is money. Soccer, at its rarefied heights, is awash with it: broadcasting deals and sponsorship agreements and corporate entertainment, all of it swilling through leagues and clubs, into the hands of players and executives and agents.

Particularly in the Premier League, everyone has grown fat on it, and now that the supply has been cut off, nobody wants to go hungry. Weeks after games were canceled and the season was suspended because of the coronavirus pandemic, long after Barcelona’s squad agreed to give up 70 percent of its salaries, long after Juventus players delayed their payment for months, players in England had still not agreed to defer or forfeit their salaries.

As of Thursday, their union — the Professional Footballers’ Association — was still locked in negotiations with the Premier League, the Football League and the Football Association, trying to strike a deal. The Premier League had advised its clubs that it wanted them to act in unison; it did not want anyone moving unilaterally.

At the same time, just as in the United States and other countries, hundreds of thousands of people in the rest of the British economy were filing for unemployment benefits, just the first wave of the economic shock caused by the coronavirus and the shuttering of towns and cities across the world.

At least four Premier League clubs, meanwhile, have moved to place many of their nonplaying staff on furlough: Norwich City, Newcastle United, Bournemouth and Tottenham Hotspur. Others will follow, perhaps including some of the richest in the game, teams that are planning to spend hundreds of millions of dollars in this summer’s transfer market now taking advantage of government support programs to pay their employees.

It is not yet a month since the Premier League was open for business as normal, not yet a month since these teams, backed by billionaires, played a game. English soccer’s broadcasters have not yet — as two networks have in France — refused to pay the latest portion of their rights agreements. Those acting on behalf of the players are surprised, it has been suggested, that the richest league in the world should plead poverty quite so quickly.

From the outside, it is a faintly obscene situation. Soccer, of course, makes a convenient punching bag at times like this, a portrait in the attic for a society unwilling to confront its inequalities. Politicians, never slow to issue moral judgment on footballers, have raged at how out of touch they are, how spoiled, how greedy, how abominably obsessed by money.

But the root of the problem is not the surfeit of money; that is merely a function of the real issue, which is the dearth of trust. The players do not trust that the clubs are not trying to make them shoulder the burden. The clubs do not trust that the players’ agents — and by extension the players — will act honorably, in the common good.

And, just as important, the clubs do not trust one another: hence the Premier League’s edict that, whatever action is taken, it should be across the board. Even in normal times, these institutions eye one another with suspicion. They believe that their rivals will, in some way, attempt to use any situation to gain a competitive edge. They are not well suited to collective action.

That lack of trust permeates the game. FIFA, as my colleague Tariq Panja reported this week, has plans to use some of its vast cash reserves as an emergency fund for clubs to dip into in their hour of need. Privately, though, officials worry that much of that money will simply vanish, lost as it percolates through national associations or is siphoned off by agents.