It’s natural to hide one’s true skill. Pool hustlers, TV writers, and sports columnists do it all the time. In The Princess Bride, Inigo Montoya duels his opponents left-handed because “it’s the only way he can be satisfied.” Unfortunately for Inigo, The Man in Black also uses his weak hand to start the duel. In the NBA, the Golden State Warriors spent two seasons hiding the most potent play in the game of basketball: one of Steph Curry or Kevin Durant setting a ball screen for the other.

Now the Toronto Raptors are mirroring the king they dethroned. One of the most threatening plays this season was rarely used, and Toronto took it right from the Warriors’ playbook. When the Raptors had one of Kyle Lowry or Pascal Siakam set a ball screen for the other, it compromised defenses, often beyond the breaking point. But the Raptors rarely used such a set-up during the season. Instead, Toronto hid the play, using it sparingly. But when unsheathed, it was as explosive as the Fire Swamp.

Toronto mostly used the play in clutch time when they needed a basket. That could be one reason why Toronto’s clutch offensive rating was second-best in the league, yet they struggled to a 14th-best half-court offense over full games. This piece looks only at Toronto’s games in clutch time, and of course with both Siakam and Lowry on the floor together.

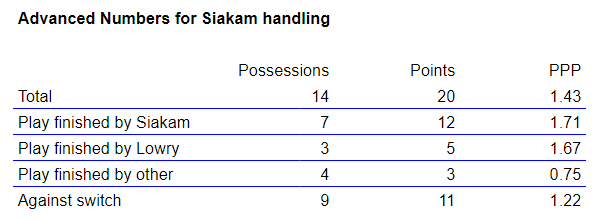

I expanded the definition of clutch time a little bit for this exercise, looking at the final five minutes of games in which the winning team was leading by 10 points or fewer. Let’s start with some numbers before we move to the nitty-gritty of the film itself. Each possession here is one in which Lowry sets a ball screen for Siakam or vice versa.

So the initial takeaway is that the Siakam-Lowry two-man game is hot fire. In games in which Toronto could use the play, they used it on average twice a game. And boy did it work. As a point of comparison, the best offense in the league this year, the Dallas Mavericks, had a half-court PPP of 1.17. Filter that further, and even with Dallas’s best lineup, its half-court PPP was 1.25. Of course, we’re not filtering for one individual play, so the comparison is apples and candied apples, but the point is that Toronto’s Lowry-Siakam two-man game is clearly an elite half-court offensive weapon. And it cuts both ways: pretty much no matter how the play unfolds, it works. Whether Lowry or Siakam is screening, or the play is concluded — with a shot attempt, free throws, or a turnover — by the handler, screener, or another player, Toronto’s PPP remains sky-high.

(All numbers here are collected by me watching these pick-and-rolls a million times each.)

Those numbers are static, but if you zoom out and look at Toronto’s season from far away, the Raptors’ usage of the Lowry-Siakam two-man game changed over time. In the beginning of the year, Toronto used it far more often. In the season-opener the Raptors used it twice against the New Orleans Pelicans, resulting in five points. They also unveiled a nifty hand-off between Lowry and Siakam, which acts as a sort of ball screen, so I included it in my data. That setup results in a hammer triple for a teammate in the left corner.

This hammer setup was regularly used by Toronto in desperate moments — after periods of drought and needing clutch triples when behind against the Boston Celtics, Milwaukee Bucks, or Brooklyn Nets. Lowry usually triggered, but the one time Siakam handled in the play, it worked to perfection. The shooter was usually VanVleet, but once I saw Toronto invert the roles with VanVleet triggering and Lowry hitting the hammer 3. It went in, by the way, though it isn’t included here.

In the third available game (the actual third game against the Chicago Bulls didn’t see the Bulls within 10 points of the Raptors during the final five minutes), Toronto went a little crazy with the Lowry-Siakam two-man game. They used it on six consecutive plays to end the game, resulting in 10 combined points, to close out their hapless opponents. Toronto used the same play down to the interior lining: Siakam set a screen on Lowry’s left, Lowry used it, and he alternated between the threat of his pull-up (established first) and his drive (established second) to sow terror. Lowry was magnificent.

Soon after the Orlando game, the Raptors mothballed the play. They used it once more against the Milwaukee Bucks and three times against the Sacramento Kings. Then from November 7 to January 28, a period of 82 days, the Raptors used the play in clutch time a total of seven times. Part of that was because of separate injuries to Lowry and Siakam. And part was because the Raptors blew out plenty of opponents and eliminated crunch time altogether. But there were also tactical reasons the play was furlouged; the Raptors preferred to use 1-5 pick-and-rolls, with either Serge Ibaka or Marc Gasol screening for Lowry, rather than Siakam. It’s a more traditional play, and Toronto’s centers are both capable screeners. The Raptors occasionally used Siakam to screen for Lowry, but if it didn’t result in points, they wouldn’t use it again. The leash was short.

Toronto still went to the secret weapon in times of total desperation, of course, such as when the Raptors needed a triple with only moments on the clock against the San Antonio Spurs.

But in general, the play was hidden, like Inigo Montoya fencing with his left hand.

That changed in a hurry towards the end of the season. From February 21 to the final pre-suspension game on March 9, the Raptors used the play a whopping 19 times, including four times against the Phoenix Suns, five against the Charlotte Hornets, four more against the Suns, and four against the Sacramento Kings. Some of that was because both Gasol and Ibaka were injured for a stretch, so Siakam was the team’s default center on offense. But they also ran the play so much more because it worked, including after the centers returned to play. In that game against the Kings — the last time the Raptors used the play before suspension of the season, by the way — Siakam handled every time with Lowry screening, which even resulted in Toronto’s final go-ahead bucket in the game.

Despite the rarity of the play, there are still a number of gleanable trends. For one, the play is almost automatic when Kyle Lowry handles and pulls up from behind the three-point line. Whenever Lowry saw a drop coverage, he rained fire. He took 4.4 pull-up 3s per game this year, ranking 13th in the NBA. Though he shot a middling 34.5 percent on them, he was deadly in the few times he launched from behind a Siakam ball screen. The seven times it happened in the clutch, Lowry scored 15 points, including his made free throws after some heady foul-baiting, giving a PPP over 2.0. Seriously, not a big sample size, but when Lowry pulled up over a Siakam screen, it was more valuable than an uncontested layup.

Notice especially Lowry’s step-back jumper against the Suns, the final in the video. His impeccable footwork and unique ability to seal his defender out of the play made this one of my favourite technical shots of the season.

One of the reasons Lowry is so successful hitting pull-ups from behind Siakam is because the latter is such a terrifying offensive player. He isn’t the team’s best screen-setter or roller, but he’s such a dynamic and athletic scorer that his presence in a ball screen causes fear. Defenders sit back on the screen, fearful of Siakam’s involvement (and also trying to force him to shoot from distance if he catches the ball). Lowry has space to wind up uncontested. When defenders hedge too high to contain Lowry, Siakam often has an easy path to the rim for a layup.

When Siakam finished the play with Lowry handling, Toronto’s PPP of 1.75 was actually higher than the 1.73 when Lowry finished it himself.

Notice, though, Siakam’s preference for patience in these plays. He isn’t an explosive and decisive vertical roller like Anthony Davis or Rudy Gobert. He prefers to play slow and have space to survey the floor. That works for Lowry, who knows how to play at any pace. But when Siakam handled, it often caused problems for Toronto’s offense, especially earlier in the season. His reads were a little slow, and if he drove, he had trouble reading the second line of the defense. He committed a few charges as a result. And because Toronto prefers to generally let weak-side shooters stand still during a high pick-and-roll, Siakam’s patience meant a stagnant offense in general.

(Very nuanced aside here, but that broken play against the Nets I thiiiink was Serge Ibaka’s fault. I’m guessing here, but it looked like that play was supposed to be a trigger for the aforementioned hammer three in the left corner, but Ibaka was in the right corner instead of the left dunker spot to screen for the hammer. VanVleet and OG Anunoby were in the correct spots for the hammer, as Anunoby was supposed to flash up to remove his defender while VanVleet dives to the corner. Another piece of supporting evidence for this theory is that Toronto successfully ran the hammer play on the very next offensive set, with Siakam handling. It worked. If my hunch is true, it’s not Siakam’s fault that he looked confused in that play.)

Siakam’s success in handling in the pick-and-roll with Lowry improved towards the end of the season. Siakam learned how to change his pace at the proper time and shift gears. He looked unbeatable against the Warriors and Kings in two late-season games. Siakam’s ability to isolate after a switch, beat a defender to the corner and cause the defense to collapse, and finish in traffic makes him probably the most threatening pick-and-roll ball-handler on the team. When Lowry holds his screen, or even flips it, Siakam wreaks absolute devastation on opposing defenses.

Siakam is also an underrated passer whether on the move or while stationary. Like all great pick-and-roll partners, Siakam is happy to invert roles and play passer to Lowry’s screener. Though Lowry missed a gimme here, Siakam and Lowry’s quick-thinking is a great example of their chemistry and general basketball intelligence.

A defense choosing to switch its guard-big defenders against a guard-Siakam pick-and-roll was sometimes exploited by Toronto and sometimes problematic for Toronto. Toronto regularly used its other guards to screen for Siakam. Siakam played plenty of time alongside Norman Powell, VanVleet, and Lowry together, and the Raptors sometimes picked whichever of the guards had the weakest defender and used him as the screener to force the switch. It was rarely Lowry who had the weak defender, so Toronto used Siakam as much as a pick-and-roll handler without Lowry as with him. This happened often in particular matchups against the Knicks and Warriors.

Against the best defenses, though, switching could hurt Toronto. As you can see from the numbers in the charts in the beginning, switching resulted in the Lowry-Siakam pick-and-roll’s lowest PPP. Particularly with Lowry handling. Size can bother him, as it limits his ability to fire those pull-up 3s he loves so well. In fact, watch his pull-up video above; both of his pull-up misses came when defenders switched. But Siakam was more successful against such a defense. A Siakam isolation against a mismatch is a good result from a half-court offense.

Two particular plays stood out from the season. In one, Siakam saw a switch coming, rejected the screen, and attacked the middle of the floor pell-mell. He finished with a buttery step-back from the midrange. In the other standout play, Lowry did the same but got all the way to the rim. Lowry had success against a switch when he attacked. Rejecting a screen, or slowing down and isolating against a mismatch are both deadly options against switches. The key to both is aggression and decisiveness.

It’s been suggested that the Lowry-Siakam two-man game could solve Toronto’s half-court issues in the playoffs. And data on the play, though limited, points towards that potentially being true. Rather than running the play twice a game, the Raptors could increase the frequency to five or six times a game, changing variables such as the screener or the handler, and even running it for other players as the primary option, such as with the hammer setup the Raptors love.

Toronto can even run the Siakam-Lowry two-man game as a total decoy to free an off-ball shooter, as they did once to great effect this season.

With both Lowry and Siakam able to pull up, drive, or isolate, as well as pass to the roller or surrounding shooters, it would seem that Toronto’s secret weapon could be the backbone of a quality half-court offense. But dig a little deeper, and that may not necessarily be the case.

The Raptors only used the Siakam-Lowry two-man game on ten possessions against the league’s best ten defenses, resulting in an underwhelming nine total points. Boston especially is equipped to stop the play. With so many similar-sized defenders, the Celtics can switch the action without offering Siakam a small to bully or Lowry a big to out-quick. (If the Celtics hide Kemba Walker on OG Anunoby or a non-Lowry guard, you can bet Toronto will repeatedly use that player to screen for Siakam.) But the Celtics had little trouble defanging the play in the regular season by sticking Jayson Tatum on Lowry before the switch.

Potential Eastern Conference playoff foes like Boston, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, and the Miami Heat are all capable of throwing elite defenders on both Lowry and Siakam. Could Lowry capitalize on, say, Ben Simmons or Bam Adebayo switching onto him? Would Siakam be better off against Tatum, Khris Middleton, or Jimmy Butler? (I think the Siakam matchups would be much more advantageous for Toronto than the Lowry ones, but I’m guessing here. I don’t think any team has more than one perfect defender for Siakam, so forcing a switch could be a solid half-court offense, but it would force Toronto into other negatives, like playing slow.) Potential advantages from switches against great defenses are minimal, and Toronto would probably not dive into that well more than a handful of times in a single game.

That’s the reality of playoff basketball, though. Advantages are minimal; no team can turn to a single play and expect a PPP of 1.58. Similarly, Toronto is equipped to detonate opponents’ pet plays. And the fact that Toronto has hidden the Lowry-Siakam ball screen and its many variants points towards some small competitive advantage. Teams will game-plan for it, but there’s only so much game-planning to be done when a team has used an individual play a few dozen times.

In truth, Inigo Montoya could only duel opponents left-handed because they were strangers. Toronto’s future playoff foes are no strangers (with the exception, maybe, of the Celtics, whom the Raptors haven’t played in the playoffs since … ever! Not once, never.) Put another way, it’s much easier for a pool shark to hustle an unsuspecting stranger than a friend, let alone one who has on retainer an entire staff to study the shark’s every move.

So it’s not like Nick Nurse and the Raptors have an ace up their sleeve. The Lowry-Siakam ball screen is not going to solve the half-court offense. But neither will it be useless. The Raptors have a dynamite foundation upon which a variety of plays can be based. When the Raptors need a basket, they will likely let Siakam and Lowry dance together. It has worked, by and large, in the regular season, and it has worked better than almost any other basketball play. If Toronto sniffs the same success with it in the playoffs, they’ll make mincemeat out of their six-fingered opponents. It’s more likely that Toronto doesn’t find that level of success. But it will work, from time to time, when they need it. And if Toronto cobbles together enough of those advantages, Toronto could well end up hustling their way past unaware opponents.