With one of their very first offensive possessions of game two, the Toronto Raptors did something new. Pascal Siakam dribbled the ball on the wing, and Marc Gasol ambled towards him for what looked like a ball screen. A big-big pick-and-roll: innovative, but not new. The uniqueness didn’t stop there, however. Without even making contact, Gasol turned and rumbled into the lane, slipping the screen before he even came close to Siakam’s defender. Siakam then drove away from the screen, rejecting it, and turned to snake towards the middle of the lane. An extremely complex action already, particularly for a team’s two bigs. But then Gasol met his own defender in the paint, sealing him while Siakam drove right past. The Gortat screen, as it came to be known after being popularized by Marcin Gortat, freed Siakam for a layup, though he chose to pass to an open Fred VanVleet on the perimeter.

VanVleet missed the shot, as most Raptors did in game two, but the play was not discarded. The Raptors used a variation of that same play — the handler rejecting the screen and the screener slipping without making contact — 12 times in game two, and the results were magnificent. In game one, Toronto asked the screener to pop more often than roll, trying to spread the floor and take advantage of Toronto’s shooting bigs. But that didn’t create many offensive advantages because Boston was happy to let one player defend the handler in space and stay with every shooter, thus keeping the defensive integrity intact. One answer for Toronto would be to let more aggressive finishers, like Norman Powell or Siakam, to handle more often in the pick-and-roll. Instead, Toronto chose to ask its bigs to roll, thus packing the paint with bodies and creating more space around the arc for shooters. Something to change the defense. But how to keep Boston from switching? Nick Nurse and staff devised something particularly creative.

Enter: the slip-reject screen.

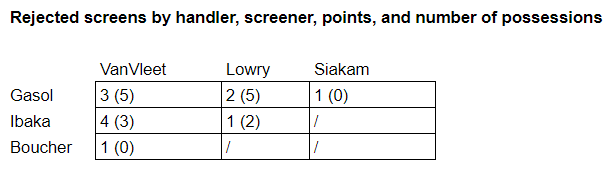

As a terminology note, from now on I’m going to refer to those plays in which the screener doesn’t make contact, slips, and the handler rejects the screen (or at least, goes away from where the screen would have been set) as slip-reject screens in order to be more concise. I don’t think there’s a real name, so we’ll go with slip-reject screen. As a note for the following graph, handlers are listed in the row on top and screeners in the column to the side. Inside the boxes, number of possessions are listed first and resulting points inside the brackets. So the Raptors ran a VanVleet-Gasol slip-reject screen three times in game two, and it resulted in five points.

In total, Toronto managed 15 points out of 12 such possessions, and they left a few more on the court with missed shots on easy looks. Seriously, if Ibaka makes an uncontested six-foot hook and VanVleet a completely open layup, — both of which are practically sure things –Toronto would have scored 19 points on those 12 possessions. There were multiple missed open triples, too. Almost every time Toronto used the slip-reject screen, it resulted in an open look. For a game in which Toronto managed only 99 points in 97 possessions total, or a mark of 1.02 points per possession (ppp), Toronto’s ppp of 1.25 on plays that featured a slip-reject were far superior. If we compare the 1.25 ppp on slip-reject screens to Toronto’s mark in the half-court, a lowly 0.90 points per play, then the success of the slip-reject is truly glaring.

Let’s dive into why it worked, who ran it most often, and the possible variations of the play.

While Ibaka and Gasol saw fairly even splits in terms of their usage in those plays, VanVleet handled in the slip-reject screen more often than Lowry. For VanVleet, such plays were an easy way to force the defense to sink on his drives, thus disallowing Boston from defending VanVleet with the big’s defender and letting everyone else stay at home. Toronto wanted the Celtics to pack the paint on VanVleet’s drives, and using the slip-reject screen was an easy way to force that while also keeping Boston from switching. Toronto needed to pry open space somehow. The slip-reject screen was the answer to that problem.

At times, VanVleet’s ability to collapse the defense resulted in open shots immediately out of the slip-reject screen when the weak-side tagged too deep into the lane.

At other times, Toronto had to work a little deeper, perhaps using one or two more actions, to find a good look. But their ability to cascade advantages, one into the next, began with the strengths of the slip-reject screen.

For Lowry, the play was slightly different than it was for VanVleet. He ran it a healthy three times in the game, and Toronto scored on each of the three possessions. He was the only handler to throw a lob pass out of the look, and that one pass somehow found Ibaka over top of the defense. Just because Boston packed the paint against the slip-reject didn’t mean they could contest Toronto’s rolling bigs in the air. When Robert Williams isn’t near the rim, Toronto will have open lanes over the defense either to Ibaka or Chris Boucher. Props to Lowry for finding the pass.

At other times, Lowry’s involvement in the actual basket didn’t result in points or an assist for Lowry, though it was his quick thinking that created the look. Here Lowry recognized OG Anunoby’s defender sinking into the lane to tag the roller extremely early. Instead of driving into that thicket or letting Gasol rumble into trouble, Lowry hit Gasol with the ball extremely early. He trusted his big to make another quick decision, and the ball ended up in Anunoby’s hands, whose defender had abandoned him at the start of the play to tag Gasol. Anunoby’s one-dribble three was cash, and this play was another good example of Toronto cascading advantages forward into an open look.

Shifting a little more of the creation job from VanVleet to Lowry could help the Raptors. Variety is of course good, but Lowry made slightly better decisions in such plays than VanVleet. VanVleet had one turnover passing behind Ibaka on the roll. But both guards are solid, and VanVleet did achieve good results. Still, Lowry could handle a few more reps in such sets. That Siakam ran the play only the once, the first time Toronto used it, was surprising. The Raptors got an excellent look out of the setup, and Siakam is more capable than either guard of finishing at the rim if Boston makes a mistake in the paint. It’s worth noting that Toronto’s handler attempted only one shot out of the slip-reject screen, a missed VanVleet layup. So if the slip-reject continues working, Boston’s counter could be to force the handler to create for himself from the mid-range. If that happens, Toronto shifting Siakam into the role would be superior; he’s by far Toronto’s most dangerous scorer inside the arc. So there are levels and counters and counters to those counters yet to happen, but I’d expect Siakam to handle in the slip-reject screen more than once per game going forward. It will be particularly useful for Siakam because switching has been able to defang his offense, to some extent.

As far as the screening went, Gasol was involved in the play for 10 out of the total 15 points, and that was because he offered so much more depth to the look. Gasol multiple times flipped the screen — the Gortat aspect of the play — to hit his own man in the paint. When that happened, the handler had an easy snake into the paint to draw massive defensive attention. Those moments always sowed chaos in the defense, and they reflected Gasol’s incredible feel and intelligence for the game.

Ibaka once tried to Gortat his screen, and it resulted in a great look, but it wasn’t as smooth as Gasol’s. Notice, for example, that Ibaka hits the guard defender, whom VanVleet had already passed. If Ibaka had taken more space earlier in the paint and then screened his own man in the lane, it would have been more effective.

Ibaka is a better finisher than Gasol, and a better scorer in general, but Gasol remains a quicker decision-maker and a better passer. The five times Toronto used Ibaka as the screener in the slip-reject screen, the Raptors managed five points. Not disastrous, but not as solid as Gasol’s 10 points in six possessions. When Ibaka did set ball screens in game two, the Raptors opted to use them more frequently in more traditional ways. Ibaka remains Toronto’s best pick-and-roll big, and his abilities to finish as the roller, in the mid-range, or behind the arc give Toronto its most diverse scoring options. Going forward, expect to see Ibaka set more traditional ball screens, while Gasol will use more of his reps in the funky slip-reject sets. They suit his strengths.

There is another way to divide Toronto’s slip-reject actions into categories beyond who handled and who screened. Toronto used such plays six times in the first quarter and four in the third. Correspondingly, they scored 28 points in the first quarter and 30 in the third. However, the Raptors used the slip-reject screen once in the second quarter and once in the fourth. They scored only 20 points in the second and 21 in the fourth. Correlation is not total causation, here, but there is enough noise that there is some level of connection. Of course, Toronto plays its starters more minutes in the first and third than any other quarter, as they start and play for over half the quarter together, and the starters are best equipped to take advantage of the slip-reject screen. But the Raptors closed the game with the starters, and they ran the slip-reject screen zero times to end the game. They also scored only three points in the final two minutes, all on free throws. An extra slip-reject screen in clutch time could have proved the difference in a game wherein offense was tough to come by.

We are talking about the smallest of sample sizes, but twelve times is a big number to run one play in one game. It worked so well because Boston didn’t have a counter, and you can expect that the Celtics will be ready in game three with something new. Still, it’s quite possible that we could see Toronto use it even more going forward. It yielded good results, and it suits the strengths of Toronto’s stars who have struggled to score against Boston. That Toronto’s handlers attempted only a single shot out of the slip-reject actions shows where there could be room for improvement. But next time you see Toronto’s centers fail to make contact on a screen, don’t be upset at what is traditionally a mistake. Know, instead, that the Raptors are trying a different approach.