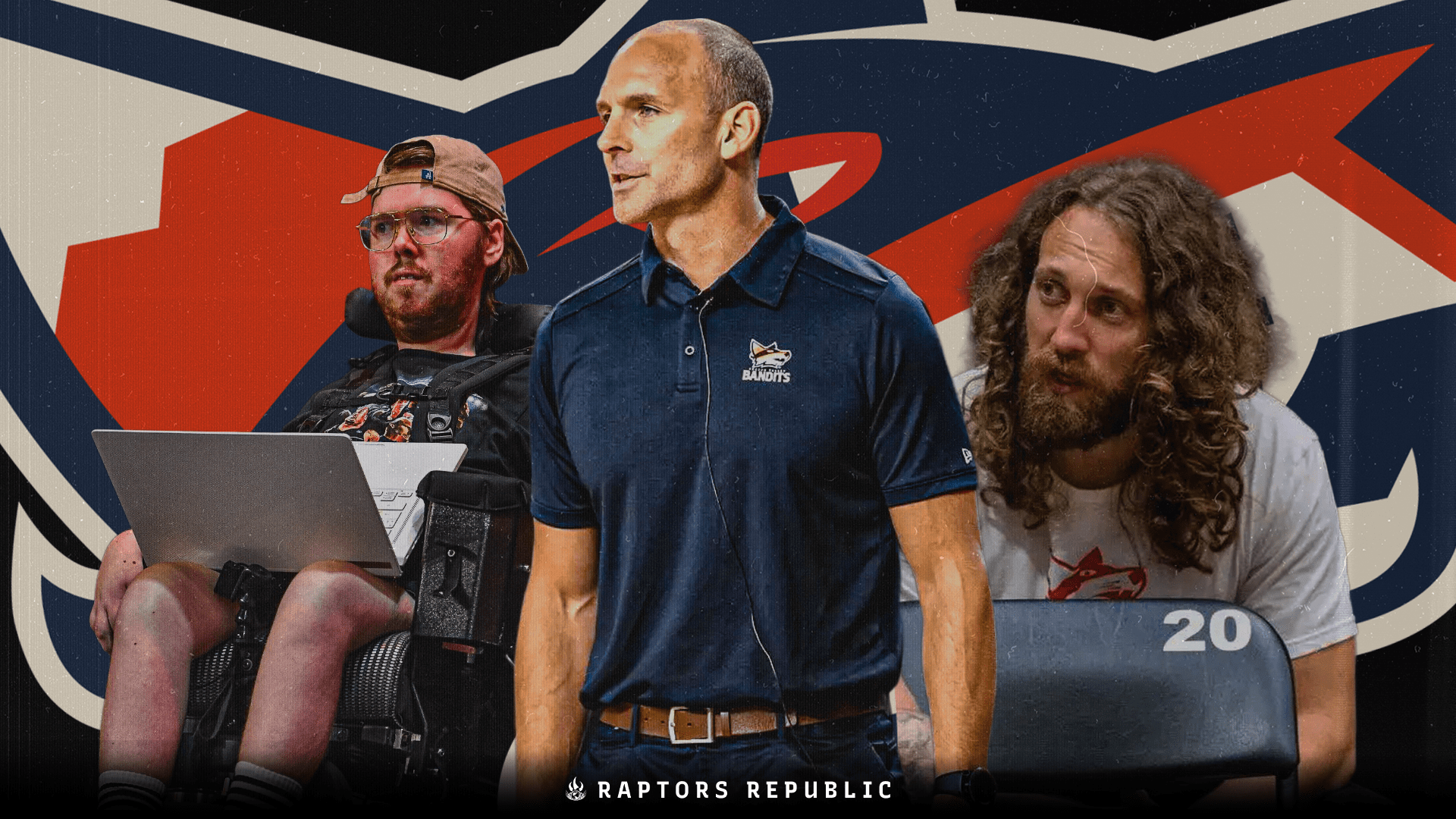

At first glance, Vancouver Bandits general manager and head coach Kyle Julius oozes out the type of testosterone and intensity you’d expect from some guy straight out of the manosphere. With a shaved head, veins popping out from his forearms, and a physique still intact from his playing days, he’s got that David Goggins-like seriousness and edge to him.

But looks are deceiving. When I asked the team’s Director of Mental Skills and Performance, Jon Giesbrecht, about how a seemingly hard-ass coach bought into the former’s mindful approach to the game, he pushed back.

“I don’t know if that’s the best way to put it. I think there’s a lot more to it,” he said. “But I appreciate that because I felt the same way when I saw his videos and all this stuff.”

When it comes to being committed to improving, Julius has shared how he isn’t everybody’s cup of tea because he doesn’t like being around others who aren’t on the same page. It’s a chip on his shoulder he’s maintained since his playing days when he had to fight tooth-and-nail to get a D1 scholarship, before going pro.

“All the work that I did on myself through sports psychology really changed the game and it was really helpful for me,” Julius told Giesbrecht when he brought the latter on board to give the Bandits a competitive edge.

And Giesbrecht wasn’t an anomaly. Vancouver’s Director of Strategy Jaxson Creasey has a goal to become a GM of a pro sports team. After an NBA agent encouraged him to learn the Collective Bargaining Agreement and introduced him to NBA executives, he spent the pandemic learning the rules and regulations surrounding the NBA salary cap.

When he spoke with Julius on the phone for the first time, the two instantly clicked. “I think we bonded over our competitive drive and relentless desire to win,” Creasey texted me.

But Creasey has never been physically able to play basketball, let alone walk nor crawl, due to a rare and degenerative neuromuscular condition. “Being in a wheelchair, many people are surprised by my interest in sports and, better yet, underestimate my ability to contribute,” he wrote to me. “Kyle always wants to hear what I have to say … He understands that I am capable of lending insight and I will be forever grateful to him for giving me a shot.”

The coaching staff Julius assembled made it easy for the CEBL’s MVP to flourish. “Mitch Creek has been literally pushing himself from every different angle to be a better human and a better player,” Giesbrecht said. “He sees the value in [a more mindful approach to the game], like being able to have some conversations, being able to be vulnerable, and open himself up. You know, work with his Ego, where he can take on some feedback.”

What is most impressive about Julius is that he has methodically created a supportive culture of dogs, where each one pushes the other. This culture has little to do with the loudness of its bark, and instead, it has to do with embracing the details required to achieve excellence – be it journaling, breathing, meditating, practicing mindfulness … simply doing whatever it takes to gain a competitive advantage.

In sociologist Dan Chambliss’ famous article, “The Mundanity of Excellence,” he demystified elite swimmers by pointing to their tolerance in consistently executing the mundane with intensity and purposefulness. “Excellence is mundane,” he wrote. “Superlative performance is really a confluence of dozens of small skills or activities, each one learned or stumbled upon, which have been carefully drilled into habit and then are fitted together in a synthesized whole.”

Giesbrecht’s specific drill illustrates the level of detail unique to the Bandits. Quiet players are often simply told that they should talk more on the floor. But telling a quiet person to “talk more” is akin to telling a dumb person to “be smarter.” Giesbrecht, who has had to overcome his own speech impediment and quietness, simulates on-court communication for quiet players, which is actually the only sensible solution to increasing that player’s likelihood of communicating more during the chaos of a game.

“Perhaps, the crucial factor is not natural ability at all, but the willingness to overcome natural or unnatural disabilities of the sort that most of us face, ranging from minor inconveniences in getting up and going to work, to accidents and injuries, to gross physical impairments,” noted Chambliss about how attention to details can often explain the achievement of excellence.

The Bandits have created an environment where working on on-court sociability, mental health, or even working out three times a day are normalized. Angela Duckworth, the author of Grit who referenced Chambliss’ article in her book, mentioned the “reciprocal effect of a team’s particular culture on the person who joins it.”

Simply put, dogs need other dogs to grow and develop. During CEBL’s Championship Weekend, the MVP award, Canadian Player of the Year, and Coach of the Year all went to the Bandits – Mitch Creek, Tyrese Samuel, and Kyle Julius, respectively.

But more than awards, their dog culture was most evident when the unexpected happened. Three calls were overturned during Target Time in the Western Conference semi-final game. Then, despite the Bandits letting the refs know they were going to foul away from the ball, the Calgary Surge kept possession, confused the hell out of the Bandits, and drew a three-point shooting foul.

That cost the Bandits their season. It was one of the most disorganized and outrageous endings to a pro basketball game, but how professionally the Bandits handled basketball injustice became a sign of just how gritty this team was.

Julius addressed the matter the next day and acknowledged that they didn’t capitalize on other chances to win the game. Creek remained so poised and professional in his post-game interview, betraying the contents of what he was saying.

The Bandits were the best team in the regular season. They’ve made it to the Finals twice under Julius (once last season), and though they couldn’t make it to Winnipeg, his version of culture-building should be a gold standard not just in the CEBL, but in the world of pro basketball.