This is Terrence Ross, owner of two NBA slam dunk trophies.

This is Kenneth Faried, a power forward who has at least 30 pounds on Ross. Colloquially known as “the Manimal”, Faried is as much — if not more — of an athletic marvel as Ross. On a fateful night in January, the two players collided on a fast-break. This was the ensuing result:

Which brings me to my premise — why doesn’t Terrence Ross attack the basket?

Let’s add some context. Last season, Ross averaged just 1.7 drive field-goal attempts per game, which ranked well outside the top-100. On those drives, he scored just 2.1 points per 48 minutes placing him among fine company in Andrea Bargnani and Kirk Hinrich.

The simple rebuttal is that Ross doesn’t drive because his role in the offense is to spot-up. That certainly explains half the story, as his average of 1.7 drives per game did rank similar to spot-up shooters like Courtney Lee and DeMarre Carroll. But Ross isn’t a run-of-the-mill shooter. Go ahead, watch that Faried dunk again.

Rather, the answer might be even simpler — Ross just isn’t good at attacking the basket.

First off, Ross really can’t attack the basket going left because he heavily favors his right hand. He’s actually not a bad ball-handler (with either hand) for a wing, as he can reasonably navigate around defenders using his quickness to offset his slightly high dribble. But, when he does drive left, he tends to pull-up instead of dribbling all the way to the hoop because he’s not a good finisher with his left hand.

This is the typical outcome when Ross goes left:

He also tends to get tunnel vision when he does drive. Ross doesn’t receive very many touches (less than 30 per game), but he averaged less than two assists per 100 possessions last season, an impossibly low figure for a wing player.

Take this play, for instance. The Magic’s defense plays it well, and stays with him to the point where he’s trapped in the paint. But instead of kicking it out to Amir Johnson for an open jumper, or just resetting by using Amir as the release valve, he takes an ill-advised fadeaway. To his credit, he nailed the shot, but process trumps results. Ross rarely creates for anyone when he does attack.

And lastly, Ross is sometimes timid when he attacks, which is strange because his athleticism should allow him to finish over-top opponents. He loves settling for the elbow jumper even when he has a driving lane. Again, this isn’t a Kyle Korver-type — Ross has the tools to finish overtop rim-defenders, or at least draw contact in his attempts.

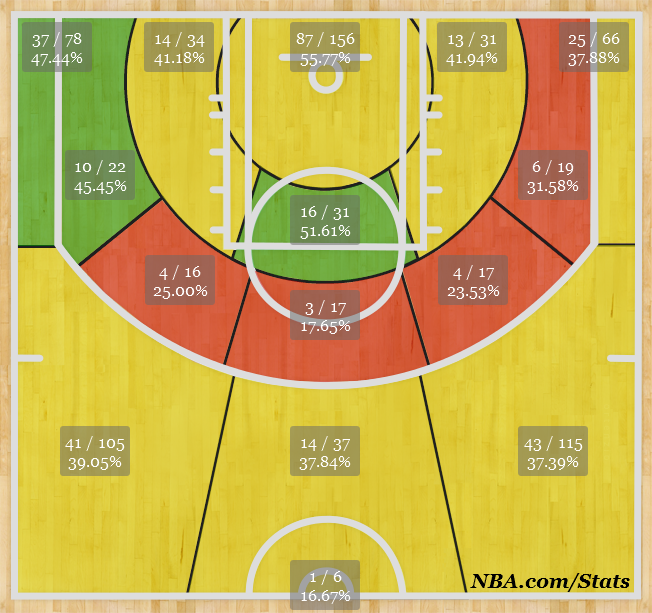

The reliance on elbow jumpers is a problem for two reasons. One, it’s not a good shot to take. To his credit, Ross doesn’t attempt too many, but that circles back to the central thesis about his driving. He’s also just not great at sinking them, albeit the sample size to draw conclusions from is rather small. The problem does seem to trace back to his rookie season too, however, as he shot a combined 19-for-61 (31 percent) from the elbows in 2012-13.

Two, Ross almost never draws fouls on mid-range pull-up attempts. Unlike his teammate DeMar DeRozan, who catches plenty of attention from referees, Ross’ jumpshot simply doesn’t yield foul shots. As a whole, Ross averaged the second-fewest number of free-throw attempts on a per-36 minute basis among all guards last season. That’s a problem for the Raptors’ offense, and it’s inflexibility puts pressure on the Raptors’ offensive schemes.

Take the play below, which unfolds much like the first GIF. The Thunder overload on DeMar’s drive, as he draws the bulk of defensive attention. When his screen play with Hansbrough produces nothing fruitful, he’s forced to reset by swinging it over to Ross. It’s an extremely basic action that almost every organized basketball team employs.

The action creates a rare one-on-one opportunity for Ross to breakdown the smaller Reggie Jackson, who to his credit, is in perfect position to help. Had Jackson reacted a second slower, Ross would have likely took the open three. But Jackson is alert, and is positioned smartly at the nail, allowing him to closeout on Ross without needing to leave his feet. But the reality is still that a defender was on the move, and Ross should had him dead in the rights, provided he could get past him.

And yet he didn’t, which speaks to a larger problem. Once the defense was able to snuff out DeMar or Lowry’s initial action, the ball would have to swing to Ross — who can’t really drive, nor distribute — which is a huge win for the defense. The Raptors then face a choice between reseting with half a shot-clock, or have Ross try to create. This is an easy choke point, something the Nets fully exploited to their advantage in the playoffs. It even helps explain why John Salmons played so much. He could at least get into the paint and create movement in the defense, albeit to a limited degree.

Improving his dribble-drive attack should be Ross’ next step in his development. There are plenty of wings that can spot-up, but they’re also limited in what they can do. Opposing defenses, especially in playoff series, exploit every weakness they can. Ross already got a taste courtesy of the Nets. Not only will it help Ross stay effective in the face of close-outs, it would also give the Raptors’ attack another dimension.

Ultimately, the onus falls on Ross to improve. The physical tools are there: he’s quick, he’s explosive, and his ball-handling skills are promising. It’s up to him to develop the next part of his game — driving, drawing fouls, hitting the open big when defenders collapse — just like his idol Kyle Lowry did. When Lowry first started, he could barely shoot threes. All he did was drive hard to the basket hoping for contact. He evolved to the point where last season, he was the second-best standstill three-point shooter in the league. If Ross were to take a similar step, the Raptors stand take a huge leap forward. Here’s hoping he does so we can see more of this next season: