Close your eyes. Truly. Imagine something with me. Picture the warm sun — wait, open your eyes, you can’t read this with your eyes closed. Okay, imagine something with me. Picture the warm sun gently toasting the top of your head, the tops of your bare arms. A breeze, the air thick, tickling the back of your neck. Maybe the burbling of a stream in the background. Things are good. Picture goodness.

And when things are good, the Raptors are back winning games. Picture them winning 45, 50, 55 games. It’s not unreasonable.

The team may be ready, but is starting point guard, recently paid, primary initiator Immanuel Quickley?

Darko Rajakovic thinks so.

“I think it’s not that much of a change. I think [what he needs to do in order for us to win 50 games is] continuing to do great things that he’s [already] doing for us,” Rajakovic said. “I think it’s just for him to find continuity of playing with us and staying healthy. And I think I would aim to see improvements with his body, that he’s getting stronger and more physical on the court. That’s pretty much it.

“He has all the talent in the world to help us [win that many games].”

In many ways, Rajakovic is right. In many other ways, he is being perhaps a touch conciliatory to one of his stars, or at least simplistic.

To be fair, the framework is there. By and large, especially over the second half of the season, Quickley has fit into the context of the Raptors without rocking the boat. His aggression has been ramping up. The shooting is extraordinary, of course. But we’re not here to discuss what he’s already doing well. The Raptors aren’t going to hit 30 wins on the season. Their star guard has to be better as a matter of definition when the team is so poor. A huge portion of that — as Rajakovic said — is playing in more games, for more minutes, and just generally being on the floor.

But it’s not all.

Most importantly in terms of skill improvement, Quickley has to get better when he puts the ball on the floor. Let’s be as specific as possible. Quickley’s inside-the-arc game is not as beneficial to his team as that of most lead guards in the NBA. There are numbers that show this. He is averaging 5.9 assists per game, which is 34th in the league, and solid. Just a tad below other shoot-first point guards like Jamal Murray and Steph Curry, both averaging 6.0 assists per game. But there are indicators that show his assists are not coming in as beneficial situations.

Of all of Quickley’s half-court assists that led to layups or dunks, five total came after he touched the paint. Such assists are hugely productive moments. Turning water into wine. That’s what point guards need to do. Quickley simply isn’t doing it very much. When he does, it looks great.

Instead, the vast majority of Quickley’s assists come from one of three categories: in transition, out of reads when blitzed in the pick and roll, or out of nonsense, non-productive passes that are ruled generously as assists. The first two categories are very helpful, but they are turning already advantageous moments into points. Those aren’t as good as creating those advantages, then turning them into points with an assist.

As a point of comparison, Murray and Curry each have several times as many assists for layups or dunks after touching the paint. And keep in mind, Curry gets off his touches much earlier than Quickley. Quickley does have fewer minutes than either Curry or Murray (though his usage rate lands right in the middle of the two of them, slightly below Curry’s and above Murray’s), it doesn’t nearly explain that gap.

Quickley is hitting the paint. As previously stated: The framework is there. His drives that end in the paint are right in the middle of Quickley and Curry, in terms of either percentage of his drives, or just on a raw per-game basis. But the high-value passing, the home-run shots that put points on the jumbotron, just aren’t there.

That could be a result of physicality. He needs to get deeper in the paint, feel more comfort in that meaty middle of the floor with defenders in all directions around him, and prolong those moments to pry open the defence with a crowbar. That happens most of all when players are bigger, stronger, and have more stamina.

There’s more, of course. The creation stuff needs to improve, but so too does the surrounding context. Quickley needs to find his moments in the game with better fluidity. It’s always hard for young point guards (and remember Quickley has only been a lead point guard in the NBA since joining the Raptors) to know when and how to call their own numbers within the flow of the offence. And Quickley is struggling there. His aggression has evaporated for games at a time as he’s tried to create for others and keep the offence flowing, but if he’s not aggressive, he’s not contributing to the offence enough simply by getting the team into sets. That balance and flow needs to clarify. It’s not entirely clear if Quickley’s future as a player is necessarily as a lead point guard. It wouldn’t surprise me if Toronto is weighing whether in the future he would be most impactful as a shooting guard, or even as an overpowered (perhaps the league’s best) bench player.

Beyond point guard-ing, Quickley needs to improve at even the things he is best at.

Quickley’s 3.5 attempted catch-and-shoot triples per game isn’t in the top 100 of the league. He’s seventh on his own team, below players like Chris Boucher and Ochai Agbaji. He is in the top 30 for pull-up triples per game (and more accurate on such shots, besides). That’s not a realistic ratio for a player of his talents, especially on a team where jumbo wings like Scottie Barnes and RJ Barrett spend so much time initiating rather than Quickley. He needs to spend much more time moving without the ball, relocating, drifting, forming up around drives. Creating jumpers without the ball in his hands. Right now it’s not where it needs to be. Or even close.

That ratio between pull-up triples and catch-and-shoot triples was the same for Quickley last year in Toronto, too. This is not a new problem. I opined about whether Quickley could hit 10 attempted triples per game before this season. He is way off, attempting fewer than seven per game on the year, prompting our own Samson Folk to beg the man to get those numbers up.

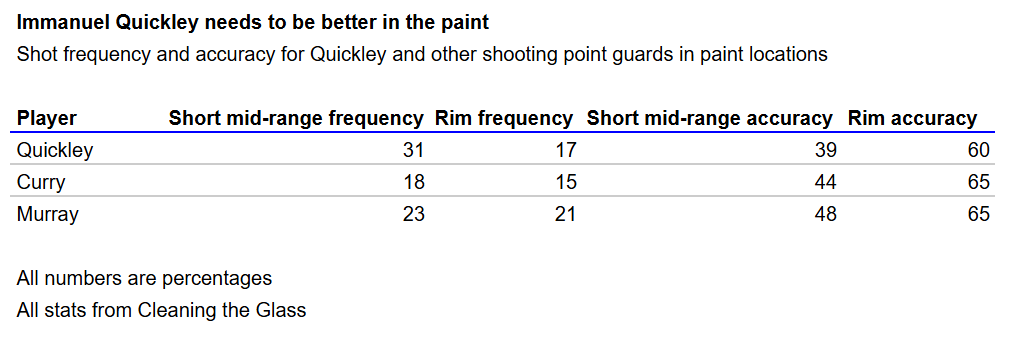

But when he’s getting run off the line, Quickley isn’t creating the highest-value shots for himself from 2-point range. Even though he’s very good at floaters (although not, statistically, since becoming a Raptor), there’s still a gap of 10 percentage points in expected accuracy between a great floater (roughly 50 percent) and a poor layup (roughly 60 percent). And Quickley takes 17 percent of his shots from the rim and 31 percent from the short mid-range. That’s not a good ratio in comparison with other high-volume 3-point marksman lead guards.

This tradeoff doesn’t just define Quickley — it defines the entire team when he plays. When Quickley is on the court, versus off, the team attempts far fewer shots at the rim and — despite his prowess — even fewer 3-pointers, too. In exchange, he has the highest on/off differential for short mid-range attempts on the Raptors. Some players pry open great shots for teammates by taking the hard shots themselves. Quickley isn’t doing that.

To some extent, maybe, I guess, this comes down to physicality. The stamina required to constantly move off ball. The strength to stay comfortable in the middle of the floor and hunt more layups. But there is obviously more at play, including the style of play in which he is most comfortable. His proclivities on the court. It’s hard to know if Quickley will ever take more layups and fewer floaters, if he will ever drive more and reach closer to the rim. It becomes much harder to win oodles of games when the lead point guard doesn’t create layups for teammates or himself. Again: Is he the starting point guard on a 50-win team if this stuff doesn’t shift?

Toronto’s other lead offensive players in Barnes and Brandon Ingram don’t create above-average rates of layups for themselves, either. Maybe this would be solved if someone did the job. It’s supposed to be the point guard. But for my money, this has to be addressed before Toronto starts trying to win in 2025-26. (I’m starting the campaign now for Toronto to offer the mid-level exception for Malcolm Brogdon — over 50-percent shooting on over 10 drives a game this season and an upcoming unrestricted free agent.)

Defence isn’t as important for point guards as the offensive side of the ball. Point guards simply need to survive. Being great is a plus, obviously. But teams can win 50 or more games with defensively limited starting point guards. (Curry, to extend the comparison, is an obvious one there.) That’s just not true for offensively limited point guards in today’s era. Point guards do need to be able to survive on the defensive end, to fit into the broader structure without completely sabotaging it. And Quickley has passed that test.

He has started to look more and more like the Quickley that was advertised on the defensive end when he was a New York Knick. He is limited on the ball but better off of it. He reads plays fairly well and can rotate consistently. The defence is, more or less, fine. Toronto has actually been better defensively with him on the floor than on the bench on the season. And since March 1, the Raptors have had the second-best defence in the league. Over the same time period, the Raptors have been equally as strong defensively with Quickley on the court as on the bench. He has proven that if the team context is good, he can fit within that. That’s good enough.

His on-ball defence does need to get better. He still gives up straight-line blowbys. That probably is untenable on a team that wants to win. (And playing next to a shooting guard that can really defend at the point of attack would help quite a bit, too.) But that’s less important than changing his offensive stripes. Which is crazy, because he’s something of an offensive specialist. But the offensive burden on starting point guards in today’s NBA is unfathomable.

All told, Quickley is close to being the player Toronto needs next season, when it starts trying (and needing) to win. He does many things well, all of which are required by the team. But there is much in his skillset that isn’t there yet. Even given 70 games of Quickley this season, the team still likely wouldn’t have been a winning one. He needs to get better driving for himself and for teammates, at creating more of his own jumpers, at commanding the offence while retaining his aggression in it. None of that is easy. But if Toronto is going to be as good as it wants to be next season, Quickley will have to figure it out.

The future of his core group together likely depends on his ability to do so.