On Content

To begin her 1964 essay Against Interpretation, Susan Sontag quotes Oscar Wilde. “The mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.“

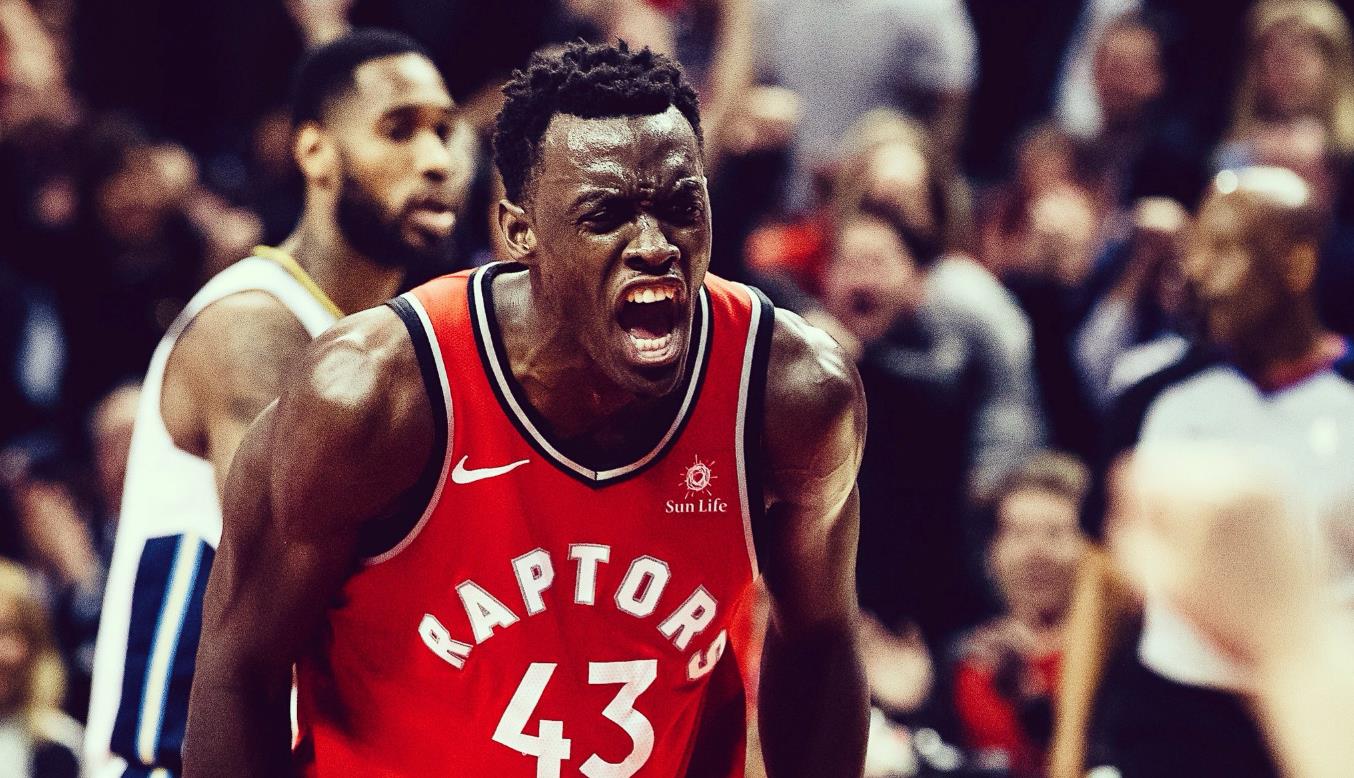

Our topic here today is the mystery—not of the world—but of Pascal Siakam, which is of course the mystery of the world in microcosm. We are going to be talking about the invisible (projections, interpretations), and we are going to be talking about the visible (basketball, basketball players). And we will be calling the invisible “content” and the visible “form.”

Sontag’s essay is critical of the attention paid by critics to the invisible—to content. Her solution is to refocus on the perceptible, that is, form.

This at least should be easy for us. The NBA is a league of incredible forms. The inverted triangle of LeBron’s torso, the parabola of Steph Curry’s jumper, the Ninja Turtle-shellness of Russell Westbrook’s lats, the pitch and warble of Kawhi’s laugh.

But what happens to a form over time is that people (pundits, redditors, talking heads) pick out pieces by which to interpret the whole, i.e. cherry-pick plot points on which to hang a narrative. This ‘content,’ generalized and thus largely invisible, slowly papers over the form. This is how a person once of flesh and blood becomes a prototype. Over time and with idealization, some prototypes in turn become archetypes: the 6’6” shooting guard, the 3-and-D wing, the undersized power forward, the unicorn.

These archetypes are the basis for our NBA taxonomy and, in part, account for the weight of expectation that hangs on young players. We see Zion Williamson and, hovering behind him, the archetypal form of LeBron James.

Kobe Bryant self-consciously measured every move of his career against the standard of Michael Jordan, not that he had much choice. Harold Miner, a high-flying shooting guard from Inglewood, was dubbed “Baby Jordan” while still in prep school. Later, his college coach at USC said the moniker was the worst thing that could have happened to him.

Still, I am not categorically against archetypes. I have a favourite. It’s the magic beanstalk, relative of the unicorn.

We all know the story. An innocent, baby-faced boy is told by his poor mother to sell their old cow. On his way to the market the boy is stopped by a strange man who says he has come from a faraway land. In this faraway land, the man says, he acquired a bag of magic beans. He will give the beans to the boy for the low price of the cow. The boy happily accepts and takes the beans to his mother, beaming with pride. She, of course, tells him he’s a fool. But she’s wrong (like Popovich about the Gasol trade, wrong, but very justified in her frustration). The beans are magic. They sprout and their stalks plunge up through the clouds to the world above.

Players who fit the archetype are foreigners (from a faraway land), who are incredibly long, and who seem to transcend certain physical limitations that the world places upon other mortals. Prime examples include Kristaps Porzingis, Giannis Antetokounmpo, and Pascal Siakam. Lacking Kristaps’s stroke, Giannis is the one to whom Pascal is most often compared, with Giannis representing Pascal’s potential ‘ceiling.’

Up until this point the use of archetypes was pure play, but the ‘ceiling’ demonstrates the oppressiveness of content. In imagining a categorical sameness between Antetokounmpo and Siakam, I have blurred both their forms slightly. Mostly it’s Siakam who is diminished by the comparison: no longer Spicy P; instead, Giannis-lite, which sounds like a drink that tastes of aspartame.

A player comes into the league and for the first few years we cannot see him at all for the content we have superimposed upon him—all the players he might one day be like, the player he himself might become. Or might not become.

These projections form a background hum: “If Siakam can develop a jump shot…” “If he can continue to improve at this rate…” “…then he’s going to be Draymond Green.” “…he’s going to be Giannis.” “…he’s going to be unstoppable.”

“He’s 24,” Respond the cautious. “He won’t continue to develop at the rate he has. Don’t get your hopes up.”

To both of these critics, I say thank you for the interpretation, but I am tired of conditionals, tired of projections both optimistic and pessimistic, tired of the intellect’s empty arrogance. As Sontag puts it, “To interpret is to impoverish, to deplete the world—in order to set up a shadow world of ‘meanings.’ It is to turn the world into this world. (‘This world’! As if there were any other).”

There is no this Pascal Siakam. Only Pascal Siakam.

On Form

(Photos by Samuel Hunter)

It was October 7th when I first saw potential turned flesh. He was practicing his Euro step with Fred VanVleet and Phil Handy when I walked into bright little Mattamy Centre for the Raptors intra-squad scrimmage. Pascal Siakam. Just fifteen feet away and shockingly real, shockingly human.

To delve once more into archetype, there is something about the soccer player turned basketballer that appeals to me. In the history of the game, my favorite player is Hakeem “The Dream” Olajuwon, he of the dream shake, he who always moved like a rare and blessed exception to the otherwise equanimously oppressive law of gravity. It’s the footwork that I like. A big and heavy man who can step lightly, who can dance around other big and heavy men, is a beautiful sight. Think of young Muhammad Ali floating like a butterfly around the comparatively ground-bound and heavy-footed challengers of his era. Think of Hakeem utterly bamboozling the otherwise-great David Robinson.

Watch the above video of Hakeem and then watch a video of Siakam in the post and you may not understand why I would compare them. Where The Dream was smooth and measured—a master of setting it up and then hitting his defender with the exact combination that would send him lurching—Siakam is herky-jerky, pure freneticism with a soft touch. The model for his back-to-the-basket game is the whirling dervish. It is undeniably efficient; his whole game is, as Joshua Howe recently described at length. But it is also, like so many other efficient things, somewhat ugly. The problem is that it is too efficient, too effective: the purely workmanlike is not beautiful.

Where we see Pascal’s footwork, where we see that hint of Dream-like smoothness, where he becomes my favourite young player—is on the break.

First, Siakam is fast. Like in this clip from the game against Golden State.

He waits until the rebound is secure, then turns and sprints past three Golden State players for the layup.

If you are watching on TV, he will often outrun the field of the screen for a few moments before someone tosses him an outlet pass, which the cameraman will follow, and ball and viewfinder together will find Pascal as he streaks down the court. If he’s not already at the rim when the ball catches up to him, he uses a beautiful in-and-out dribble to keep defenders on their heels. He finishes creatively, either by jumping from distance and outwaiting any challenges in midair or by finding an angle and a touch that dampens the momentum of what is often a full sprint. He displays a little extra bounce and reach in these circumstances, enough to go not just over but almost around his defender to the glass, which he can use with phenomenally soft touch.

But Siakam running, catching, and finishing in transition is merely fun. When I love him best is when he gets the rebound and leads the break. When he jumps with those long and still-a-little-skinny arms stuck way up in the air, and the ball settles in his long hands. Before his feet regain the ground, his eyes are upcourt. If he’s not in a crowd, he tosses the ball out ahead and sprints onto it. His body tilts forward as if he is running into a strong wind.

This is the visible, the form. Not the potential all-star berths, nor his shortage of touches. The visible is Pascal Siakam leading the break, smiling. There is mystery in it, and joy, too. Indulge.

Disagree? Fight me on Twitter.